In every blockbuster franchise since “The Matrix,” the looming presence of artificial intelligence (AI) is regarded as something to be feared. With recent advancements in AI-powered language and visual generative programs, this fear is felt at an exponential rate.

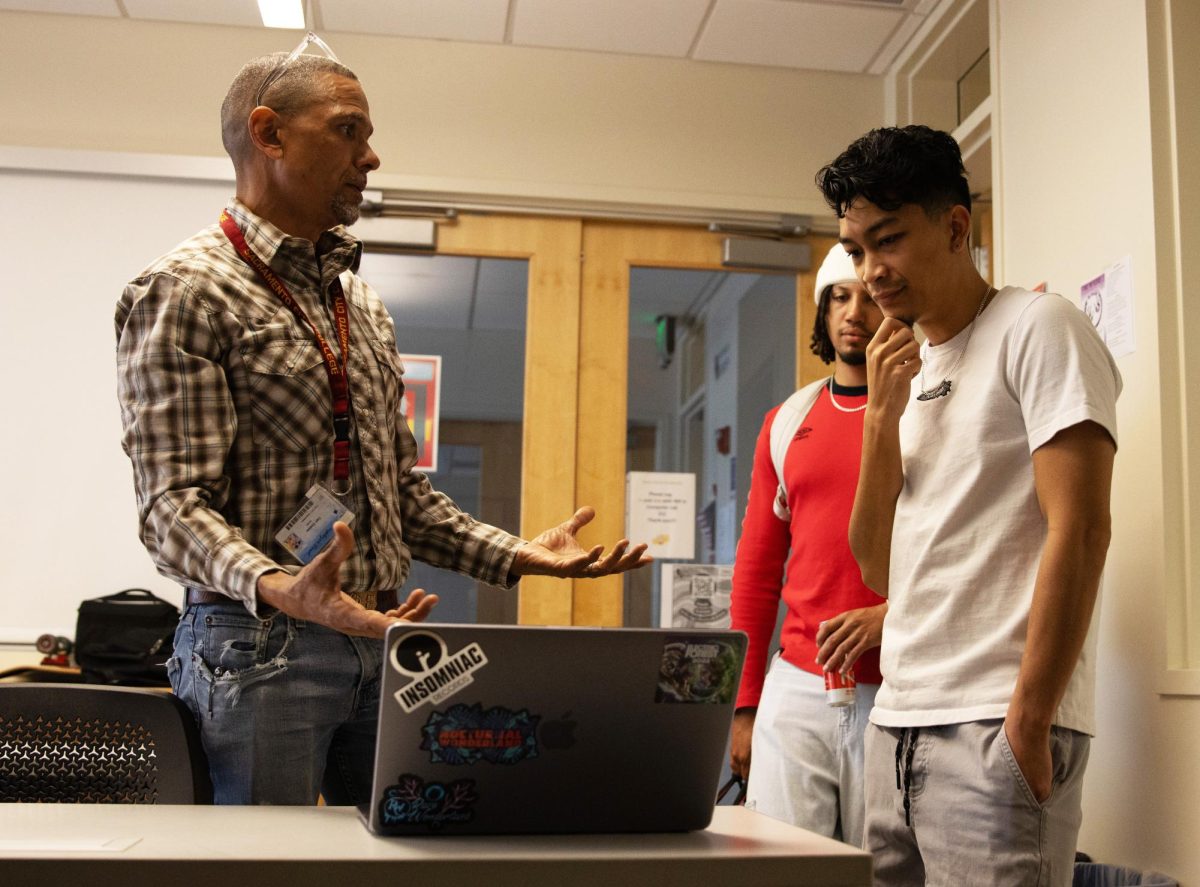

Patrick Crandley, a design and digital media professor at City College, thinks we should embrace AI on our campus — even as he acknowledges some of the potential problems.

“There is a Mount Everest size pile of concerns when it comes to working with AI in the classroom,” Crandley said. Despite this, he believes that AI can positively change the learning process, and even enhance what students can learn and create. “I directly support its inclusion in our academic environment.”

This isn’t the general consensus of all of City College’s educators.

At City College, professors started noticing the use of language model-based chatbots to complete work in the spring semester of 2022. The most popular programs that students use are ChatGPT and Bard. The main concerns professors have about AI’s presence in City College classrooms are a lack of critical thinking, plagiarism and the ethics of the new technology.

Over the past seven decades since the invention of the first AI program, which was originally used to play a game of checkers, the capabilities of the technology have exponentially grown. AI has left the realm of science fiction and now stands at the threshold of redefining a cornerstone of humanity: humanities.

However, several City College’s humanities educators can vouch for its potential.

Dawna DeMartini, an English professor at City College for 17 years and the vice president of the college’s Academic Senate, sees the inclusion of AI as something that will objectively train students for the workforce. In fact, DeMartini included an assignment in her intro-level English class that involved refining an AI generated prompt.

“[In] every single industry, [AI is] already being used in some way and will very likely continue to be used,” DeMartini said, adding, “And if we’re at [a] community college, and our whole purpose is to educate students, not singularly for their career, … then incorporating AI is helpful.”

AI is also being viewed as a tool to increase accessibility. Crandley believes that AI can even allow non-artistic students to have a voice in humanities. “I think [AI is] an enabler in every sense. It allows folks that maybe don’t have that god-given talent to be a sculptor to still be able to communicate in sculpture,” he said.

Another way AI can increase accessibility is by bridging language barriers. Holly Piscopo, a history professor, said, “I think AI can be used really really well, and by students to do their research sometimes, and I think it’s great in terms of expanding into other languages as well.” In the context of a history course, AI could possibly allow students to more freely explore artifacts and texts globally.

However, some professors are still hesitant to allow the inclusion of AI in the classroom. Dana Maureen, an English professor, explained that she wants to teach students to think critically when writing and reading. While she does not allow students to use AI in her classes, she is open to the potentials of the technology.

“I think the thing with it is that it’s still new. I am still figuring out how it can benefit me and my students from a pedagogical perspective,” Maureen said.

As part of the Academic Senate, DeMartini and her colleagues are assembling an AI task force to guide all departments in navigating AI in the classroom. In an email from Lori Petite, the past president of the Academic Senate, Petite wrote “the purpose of this committee is to explore the applications, benefits, risks, and ethical implications of integrating artificial intelligence at SCC.”

Conversations surrounding AI are as endless as the technology itself. Some highlight the good, while others focus on the bad. Perhaps the biggest worry is that AI is going to replace the “soul” of our arts and humanities. But the college’s humanities professors at City College believe a human’s inherent need for authenticity will keep the arts soulful.

“I was thinking about what touches us, right? And there’s something about the human touch that I just think is brilliant and beautiful, and AI hasn’t been able to quite do that yet … I’m [a] pretty optimistic person in general,” Piscopo said. “Even though I’m a historian, I don’t believe in the ‘good old days’, and I really hope we go forward with ethics as our intentions.”

DeMartini pointed out an AI generated flier that was created to advertise a show that her brother’s band played. The poster pictures a group of young 20-somethings at a club, laughing and enjoying eachothers’ company. It’s a little too picture perfect the same way staged stock stock photos are, and jarringly uncanny.

“I was looking at this, and I realized human beings have a drive to express themselves,” she said. “When people make art, when people use language, we are wired to communicate. We are social beings. We want to share who we are, our experiences, our points of view. I feel like the threat [is] that AI will take over visual arts, creative art, and writing, but we won’t be attracted to that.” DeMartini posits that AI generated art does not compete with the authenticity of human art.

“I want to trust in humans and our humanity that we will all still both want to create, make art, use language, make things,” DeMartini said.