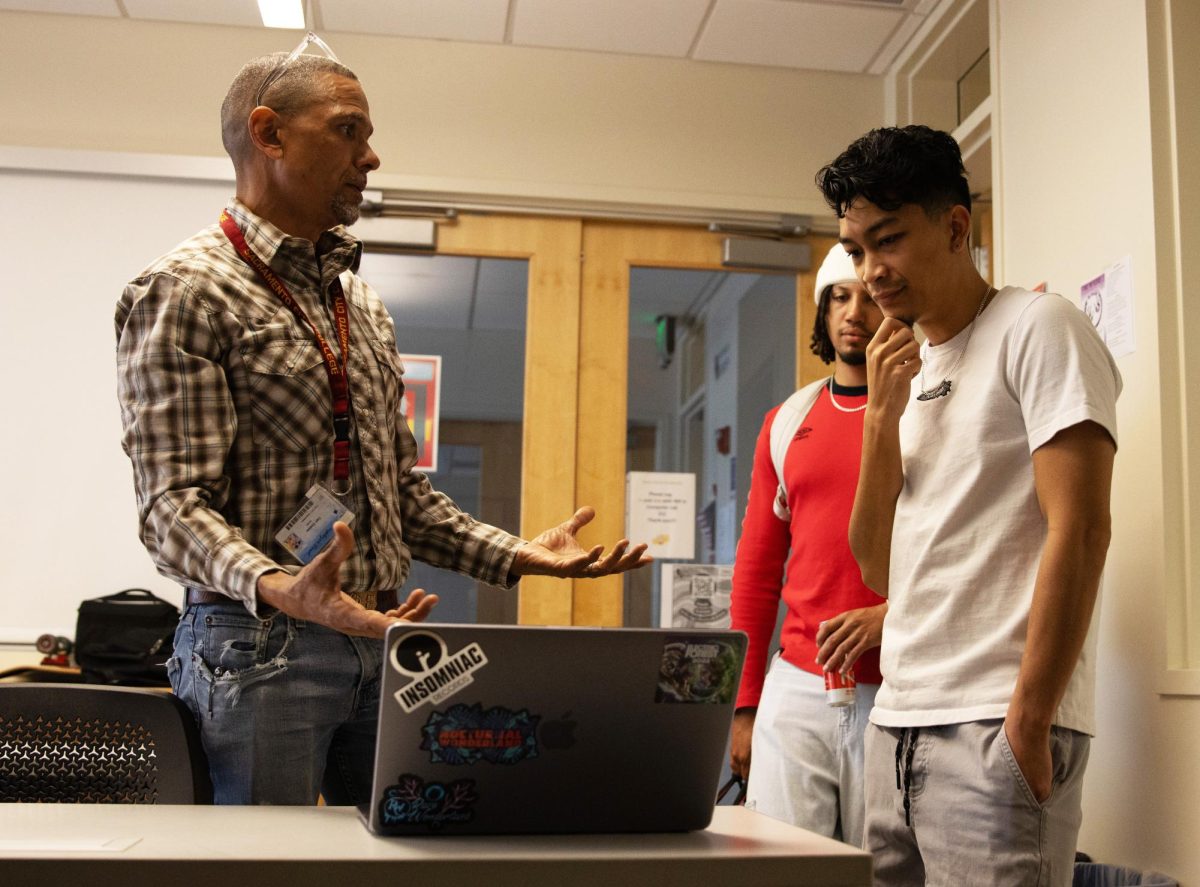

It’s a windowless room with just enough space to stack two compact sedans side by side. A four-person study table sits in the far-left corner, along with a metal bookshelf containing general-ed textbooks, sociology texts, a stack of old-model laptops and boxes of snacks. When new students step into the room for the first time, the first thing they come across is clerk Julie Correa’s desk, and the first person they see is Chris Kelly. He sits at the study table, leaning back on his chair, talking to other students. One of the students is Jacque Brown, who is peering through her glasses at a laptop. A wall-size logo looms over them—a cuffed hand, its chains broken, clenching a pencil.

Kelly quickly rises to meet the new students. This imposing figure—6-feet-4 and 240 pounds, sporting a goatee, tank top and thoroughly tattooed arms— introduces himself as “Chris,” one of the student interns.

“Come on in,” he says. “Come on in! Have a seat.” He reaches for a chair. Brown stays in hers, beaming at the newcomers.

Located on the first floor City College’s Rodda Hall South, Room 163 is the home of the Re-Emerging Scholars, or REMSCO, for short. Here, formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students, led by City College sociology professors Shane Logan and Nicholas Miller, work together to make achieve changes in themselves and their community.

When REMSCO student mentor and intern Martin Montoya first stepped onto the City College campus for the first time last year, he remembers feeling so lost and out-of-place that he immediately wanted to leave.

“I couldn’t pick out nothing. I didn’t know where to start, what building to go to or anything,” says Montoya. “So I just kinda got scared. I walked around for a minute and I was like, ‘I can’t do all this.’ I just left.”

Many formerly incarcerated students have similar experiences when coming to college after spending years out of school or behind bars, according to Kelly. They’re unfamiliar with new technology, how to register for classes, how to fill out a financial aid application, or how to look for the help that they need. What is a natural process to many students who have been continuously in school or have come out of high school with college counseling, can be intimidating to formerly incarcerated students.

“[They were] intimidated by the lack of cultural capital that lots of people take for granted,” says Kelly.

It was with Kelly’s help that Montoya came to college.

“Chris walked everywhere [with me]. I mean, he walked to the bathroom with me, he went to the library, he got my ID with me, he went everywhere,” says Montoya. “Every time I came here, he would, like, meet me over here by the fountains, and I’d walk up ’cause I didn’t have to like look around for nothing.”

One of the biggest obstacles in going to college for many formerly incarcerated students is believing they can do so. Montoya says he didn’t think college was possible until he met another formerly incarcerated student Bradon-Dale Fellows, who told him college is, indeed, open to people like them and that education had transformed his life.

It is this message that Fellows, now a REMSCO outreach intern and mentor, takes to the clients of re-entry organizations that he visits on Friday.

One of these locations is the Sacramento Drug Court. It was where Fellows first met REMSCO advisor Shane Logan two years ago. Until meeting Logan, Fellows says the thought of going to college had never occurred to him.

Between his incarceration at 17 and release at 24, Fellows had been told that he was nothing more than a prisoner and a convict.

“That I wasn’t good enough, that I was never going to amount to nothing,” said Fellows. “That being a criminal was what I was and what I was good at. And that’s pretty much as far as my life was going to go.”

The next 10 years after his release, Fellows went to school to work in construction, worked at various positions at restaurants and as a tattoo artist. But Fellows says he was never happy with the work he was doing.

“When you get out on parole, your parole officers aren’t like, ‘Hey, why don’t you go to college?’,” Fellows recalls. “They don’t give us the opportunity of like, ‘Hey, you can be more.’ No, [they say], you need to go get a minimum wage job and stay out of jail.”

The day Fellows met Shane Logan at the Sacramento Drug Court, Logan was giving a presentation about a program he and Nicholas Miller were building to support formerly incarcerated students at City College.

Logan had brought with him a student named Josh King, Fellows recalls, who left a lasting impression on him.

“This light just came on me,” Fellows says. “Like, I’m looking at this guy who did over 25 years in prison, and now he’s a college student, and he’s working towards giving back to people like him that need that help and need that guidance,” said Fellows, who became one of the first waves of students in the program.

The program they were building, of which King was then apart, was the Re-Emerging Scholars Program at City College.

•••

At around that time, in November 2017, according to Miller, he and Logan had been reaching out to probation and parole field offices to tell them about the program and the value education had for their clients. They were encouraged that more referrals were coming in. Logan and Miller sent then-REMSCO club president Foy Reynolds to gather people on campus to bring college services to the students, instead of the other way around.

Reynolds recalled, “My job was to establish a list of on-campus resources, and who’s in charge of them, so we can consolidate them and bring these people here and take care of the admissions and records, financial aid, all this stuff, at one time.”

In the months before, Miller recalled that he and Logan proposed the program to the college. They set up meetings to present their concept to City College administrators and the Academic Senate.

There were some faculty who opposed it, according to Logan, raising questions such as, “Why are we giving these resources to those people when our students already need help? Why are we dedicating these resources to formerly incarcerated? Why aren’t we doing this for our regular students?”

However, those kinds of questions were rare. The college community was generally in favor of the program, including President Michael Guiterrez, Miller said, who was “really excited and supportive.”

“Some people like to believe that ‘once a criminal, always a criminal,’” said Miller. “We absolutely don’t see it that way.”

Miller and Logan believed that formerly incarcerated students had great potential and were assets to the community, even when the first group they brought on campus had low passing grades.

“They were the most motivated, rock-star students that I’ve ever had,” said Logan. “[But] their success didn’t match their motivation and enthusiasm, and it was because they were dealing with all of these outside factors.”

Logan said many were dealing with food and housing insecurities and parole restrictions. Many had grown up in environments in which they weren’t taught the skills and behaviors—“the hidden curriculum,” in other words—necessary to be successful in an academic and professional world. When these students had failed in primary and secondary school, there had been few safety nets (after-school programs, private tutors and others) to retain them.

“It’s like having a really enthusiastic plant that’s in the wrong soil,” said Logan. “You’ve got this plant that is capable of becoming a giant oak tree, but it’s in some soil that isn’t conducive to their growth. It needs to be transplanted — planted into a better soil and given a little bit of, you know, nurturing, and then it’ll just take off.”

According to Miller, every semester since 2017 he and Logan increased their efforts to expand the program, working outside of their teaching duties. They began a Re-Emerging Scholars club and support group for the formerly incarcerated on campus. By spring 2018, they began a 1-unit learning community class for their students to regularly check-in. A few semesters later the learning community became the REMSCO cohort with a 12- and then 15-unit curriculum that takes students through most classes required for transferring to a four-year university.

•••

This fall semester, REMSCO students came to the check-in class on Tuesday. Instructors Logan and Miller met them at the door and greeted them as they came in. When class began, the students took turns sharing how their week had gone. Relaxed and conversational, the class knew its instructors as “Nich” and “Shane,” and f-word intensifiers were not a problem. Logan and Miller, in their REMSCO T-shirts, khaki shorts and running shoes, stood at opposite sides of the room, taking turns addressing the students.

“It was a class that facilitates us having weekly conversations with them,” said Logan, “where we could start having these conversations about how to overcome some of these problems that they’re experiencing.”

“[Shane] is just hella funny,” said REMSCO student intern Marcus Erba. “He gets the material done, but in a way where, like, you know, we’re having a good time, we’re having a conversation.”

Nineteen-year-old Judith Marquez recalled coming to check-in class one day last summer feeling overwhelmed with negative emotions. She had been struggling in her recovery program and would have gone away from class without talking with anyone, except that when she got up to leave, she had felt a slight kick at her shoe. It was Logan.

“He’s like, ‘Come on,’” said Marquez, gesturing her head toward the door as Logan had, urging her to come outside to talk. “Shane’s always kinda like — he doesn’t like to baby us.”

“He could tell that something was going on,” said Marquez. “He brought me out and was like, ‘You know I’m here for you’ and (all that). And then I kind of just broke down to him.”

Marquez told Logan about her struggle dealing with her emotions, and the harmful thoughts that she had been having.

“I could tell that he genuinely cares about me because he was like, standing there and grown-ass Shane—he was like, about to cry,” said Marquez. “Like, no, he didn’t want that for me.”

Marquez said Logan would have talked to her longer if she had not had class. He suggested some coping techniques and readings, and kept frequent contact with her over emails.

Marquez said Logan would always try to keep in touch with all his students.

“He likes to celebrate my victories,” said Marquez, “along with everybody else’s, you could just tell he genuinely cared about it.”

•••

After the check-in class ended, a portion of the class stayed for club meetings. The two clubs—the Re-Emerging Scholars club and the Sobriety Society club—take place each semester on alternate weeks.

Started by Marcus Erba, the Sobriety Society provides a support group for those in recovery from substances. Student Courtney Foston joined Erba as co-facilitator. Both have been in REMSCO since summer 2019.

Foston and Erba both grew up in the area and graduated from high school within a year of each other. Erba grew up in Woodland and played soccer and baseball in high school. Foston sang and performed in theater when she got to American River College. But, she added, school seemed pointless.

“I didn’t have a direction that I was going in. I was just kind of doing it because I was told to,” said Foston. “I’d just graduated high school, and it was just expected.”

In college, Foston rarely showed up for classes, except to participate in musical theater. After two semesters, she was placed on academic dismissal.

“I was tired of pretending to do these things and have these dreams I don’t have, aspirations I don’t have, just to put on a show for my family, just to appease them,” she said. “In the long run it didn’t feel like I was doing anything with my life. I felt empty, really. I couldn’t do it anymore.”

For Erba, he became disillusioned by formal education earlier. Though he was deemed a gifted student in junior high, appearing smart back then was one of the last things he wanted.

“I remember I was super embarrassed,” said Erba. “’Cause I didn’t wanna be smart.”

He would purposely underperform in school to fit in. “The cool kids,” he said, “don’t do good in school.

“That’s just like a metaphor for my whole life,” said Erba. “I had an idea of who I wanted to be, and it wasn’t matching up with who I was. So I was constantly in this conflict.”

Erba started using drugs when he was 14. The next 12 years, he said, were a constant battle with addiction as he used everything from methamphetamines to heroin.

“Up until three and a half years ago, I was in and out of prison, in and out of jail, and in and out of rehab, just struggling with addiction in general,” said Erba. “I’ve been homeless, severed ties with my family, all of the fun stuff that comes with that lifestyle.”

He felt at the time, said Erba, that he would never have a “normal” life again. He’d lost so much time that he could never reach the place where he thought he should be. The transition from rehab to jail to prison had become natural.

“In the beginning, it was kind of a big deal,” said Erba. “And then over time, you’re like, ‘OK, this is just like a part of who I am now.’”

When Foston was released from jail in October 2018, the hardest part of re-adjustment was dealing with her addiction to heroin. She had been using heroin during her eight months in jail to keep her mind off her surroundings.

She took methadone to help with her addiction problem, but, she said, recovering from addiction was like going through PTSD. Knowing she could not do it alone, Foston sought help in a treatment program. But the program didn’t help her much either.

“What helped was my kid getting suspended [from school],” she said.

Her then-4-year-old son had lost his father in December 2017, when he died from an overdose. Foston turned to drugs, and not long after that, she was arrested.

“It hurt me to know that [my son] was hurting so bad and acting out enough to get suspended in kindergarten,” said Foston. “Who does that? Like, he goes to a Montessori school.”

It is with her son in mind that Foston said she seeks to make a difference in both of their lives.

“I have a now 6-year-old who, at the time, not only lost his best friend — his dad — but his mom wasn’t around to help him through that.”

Breaking “the vicious cycle” — of addiction and incarceration, said Foston, requires something she wasn’t sure she was capable of.

“I needed something different,” said Foston, “and I didn’t know how to do that. I didn’t know if I could do that. Like, change.”

•••

Growing up without a father, and with a mother who was often absent from home, Bradon-Dale Fellows recalls that as a teenager he was free to do whatever he wished, and he chose early to lead a life of “destruction and chaos.” When, later in life, he decided that he wanted to work toward a career in the rehabilitation and re-entry of violent and troubled youth, Fellows was thinking of his own experience growing up.

“I didn’t have anybody in my life that was there to kind of guide me in the right direction or teach me the fundamentals of being a responsible man in society,” says Fellows. “I started gangbanging and using drugs around the age of 12 or 13.”

Fellows says he’d never felt that he belonged anywhere. His family moved constantly. He had only a fleeting sense of belonging when he played football in high school.

“I always felt like something was missing in my life,” said Fellows. “I started rebelling and acting out at a young age.”

One night friends picked him up in what, unbeknownst to Fellows, was a stolen car, one owned by a federal judge. When they were caught and the court sentenced him to seven years in a federal penitentiary, he was not yet 17.

When Fellows was released from prison at 24, his mind was preoccupied with the desire to make up for lost time—to have fun, in other words. Then soon after, when he learned that he was going to be a father, the news, he says, put him into a “world of pain.”

“One of my biggest fears was being a father,” said Fellows, “that I wasn’t going to amount to it, that I didn’t have it in me to be there for another human being because I didn’t know what it was like to have a father there for me.”

When the prospect of fatherhood presented itself, Fellows says he tried to run from it. He turned to drugs. After his daughter was born and left with her mother, Fellows sank into addiction and returned to rehab for a second time before meeting Logan at the Sacramento Drug Court and coming to REMSCO.

The cycle of addiction and relapse is a common story for people like Erba, Foston and Fellows, a painful one they all know well.

Erba was 27 when he was released from prison for the last time in August 2015. With the help of his parole officer, he returned to rehab and didn’t use drugs for a short time, but that didn’t last long, because what he really needed, Erba says, was for him to “work on myself.”

“When you’re a drug addict or an alcoholic, it’s a state of mind, right? It’s a mental disease,” says Erba. “Just because I stopped drinking or I stopped using drugs doesn’t automatically mean everything’s going to be fine.”

After he relapsed, he was removed from rehab and the transitional program that had provided him with housing. One day in February 2016, Erba found himself sitting alone in a “sketchy” little hotel room, isolated from his family and support, pondering whether he would return to his old ways or continue fighting to change.

Erba says he lost the battle that day.

The next time he was conscious, Erba found himself in a hospital intensive care unit, the inner part of his arms and his wrist badly scarred as a result of multiple surgeries to fix his self-inflicted wounds. He wouldn’t be alive if his parole officer hadn’t kicked down the wrong door—his door—while searching for another client who happened to be staying in the same hotel, in the next room. Erba was in a drug-induced psychosis.

•••

If carrying every day the stigma of having been incarcerated is hard, having to fight addiction, homelessness and the negative forces that seek to dehumanize people is many times harder, note those who work with the REMSCO students.

City College English Professor Jeff Knorr, who began teaching college composition to the REMSCO cohort in spring 2019, says that his formerly incarcerated students inspired him with their positivity in facing a system bent on taking that away from them.

In RHS 163, three of them—Brown, Kelly and Erba—now sit around the study table.

Erba is sitting in the clerk’s chair, typing on his phone. They have been talking about someone Brown used to know. Once in a while, the conversations take on a note of solemnity.

“People can change,” says Brown. “Do you believe that?” suddenly curious about what an outsider might think of them.

They sometimes jokingly refer to themselves as “a roomful of criminals.”

Ironically, according to Logan, there are still some on campus who believe just that — that the formerly incarcerated in the Re-Emerging Scholars program are still criminals. Those people don’t wear their beliefs on their sleeves, Logan says, but would quietly discriminate against them.

But at least among themselves, the answer is clear.

“People can change,” replies Erba, interrupting the silence, looking at no one.

“People can change,” he repeats. “Otherwise, what’s the point of all of this?”

For Brown, Kelly, Erba, Marquez and others, some of the greatest gifts of REMSCO are the peer support, friendships and relationships they now have. It’s knowing that they don’t have to go through it alone—whatever it is—to apply for financial aid, to get through a difficult class together, to overcome a personal issue, or to continue the battle of staying sober. It has meant having someone to talk to who can relate to their problems, who has been through recovery and through the same struggle.

“It gave me a bunch of people that are just like me,” says Erba, “to learn from and hopefully help in some capacity. And it’s like a family, really.”

Fellows said that for him real, permanent changes began with education.

Change also brings with it a new cycle, one that now involves marriage, family, and career.

When his kids get out of school today, Fellows would be there to pick them up and take them home, to a house of their own. Then he would get them “fed, bathed, and in bed” before starting his homework. At some point in the night, he would prepare their lunches for the next day.

Winning custody of his now-12-year-old daughter was just the beginning.

“She has these expectations of me because I wasn’t there when she was younger,” says Fellows. “So I’m battling that—those feelings that she’s dealing with.”

She is now almost the same age as when Fellows, growing without his father, began taking to the streets. He hadn’t been there for her early years and would have to make up for it by trying to understand her perspective, by looking back at how he had felt.

“I no longer have to look at my past as a regret. Rather today I can look at it as an asset,” said Fellows.

In the coming year, Fellows says he will be married. Next fall, he hopes to join former REMSCO student Josh King at UC Berkeley. Looking back, Fellows says it was education that has finally made the difference in his life.

“Because classes taught me structure, taught me balance, taught me how to be responsible. It taught me to be independent, taught me how to be confident in all those things I never really learned because when I should’ve been in school, I was running in the streets.”

He feels grateful, he says, for the part that Logan and Miller played in helping him become who he is today.

“Just watching them as individuals has helped me learn how to become a man and a father,” says Fellows.

•••

When Courtney Foston completed Professor Jared Anderson’s public speaking class last summer— one of the two summer classes she took after having been away from school for over 10 years, she knew whatever grades she came out with she deserved, because Anderson, Foston says, was not going easy on them.

“I’ve got A’s in all my classes,” says Foston. “I got A’s this summer. I’ve still got A’s now. Like, I’ve never done that before.”

Thinking about that summer class, Anderson still recalls a particular moment that impressed him. It was the first time the students gave long speeches in front of the class, according to Kelly.

Students are generally nervous about giving their speeches, explains Anderson, but one student in Foston’s summer class was suffering from high anxiety.

“She was getting nervous, and she forgot what she was going to say, and it looked like she was about to give up and quit the speech and sit down,” says Anderson.

“And this student giving the speech was not in the Re-Emerging Scholars program, but one of the students from the Re-Emergence Scholars program went up and just stood next to her while she gave her speech to be supportive.”

REMSCO students Chris Kelly and Judith Marquez identified the student who went up to help her classmate as Courtney Foston.

Anderson says Foston has set a great example of how to be a supportive classmate.

That’s how Logan hopes that people will see his students as they are now—selfless, responsible members of society—and not be blinded by who they have been in the past.

“These are students that have made mistakes just like we’ve all made mistakes. They have paid their debt to society,” says Logan. “They have, you know, done everything that has been asked of them. And now we just need to give them a leg up so that they can re-enter society and be more successful.”