When Dawna DeMartini thinks of late City College philosophy professor Tanya Rodriguez, she remembers her strength and bravery.

DeMartini, an English professor who worked with Rodriguez in City College’s STEM Equity & Success Initiative, first remembers seeing Rodriguez at an academic meeting several years ago, where Rodriguez spoke about supporting the college’s students of color.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that was rad,’ because she was untenured,” DeMartini says. “I would not have been as brave to bust out like that.”

DeMartini says she leaned over to the person next to her and asked who Rodriguez was and what she taught. She was surprised to hear that Rodriguez taught philosophy because she says Rodriguez was not the stereotypical image of a philosophy professor.

“I thought about that all the time. Even before she passed, I would think back and think I need to be that courageous and use my voice and risk, even if it upsets people,” DeMartini says. “Someone said this about her: ‘She was on the right side of the fight, always.’ We know who we are fighting for: our students.”

Rodriguez drowned at Folsom Lake Aug. 1, while swimming near Beals Point with her 6-year-old nephew, who was later found wandering around by passersby. She had worked at City College since 2015, and her death, at 49 years old, has weighed heavily on her colleagues.

‘Inspirational in her courage’

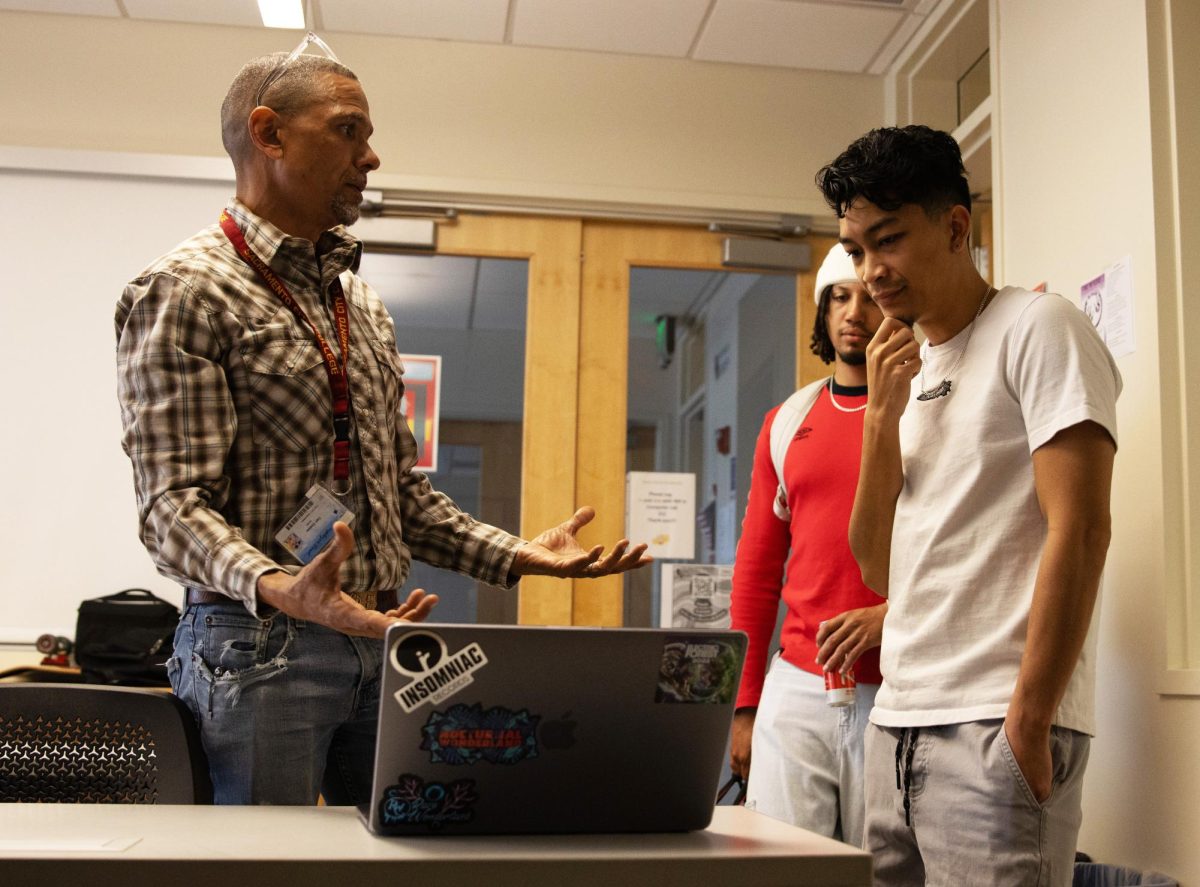

Martin Ramirez, the director of the STEM Equity & Success Initiative, describes Rodriguez as a professional who was willing to take risks.

“She did not shy away from professional development. She was in there with us,” Ramirez says. “She had the courage. She had the audacity to hang in there and try different things. Sometimes faculty members that have doctorates show up a couple times [to meetings] and don’t do anything because they already know everything.”

Rodriguez, though, knew that there was always room to grow, he says.

“Sometimes people think that change is not possible, and she was the opposite of that,” Ramirez says. “She was a believer in change and learning.”

DeMartini echoes Ramirez’s view of Rodriguez’s enthusiasm about making changes and implementing new techniques in education.

“She was inspirational in her courage. It was about showing what it looked like to be a courageous instructor who is like, ‘I know these are the rules, but I don’t care,’” DeMartini says. “A lot of us are like, ‘I don’t know. Am I going to get in trouble for trying this new thing? I don’t know if I want to do something that’s so radically different.’”

Riad Bahur, a professor and coordinator in the history department at City College, reiterates DeMartini’s reflection on Rodriguez. He didn’t know Rodriguez well, but he was struck by her bravery at equity committee meetings.

“She was really brave in taking positions that were unpopular with at least part of the senate membership, and I was really struck by her and her willingness to be vocal about issues affecting students of color and institutional policies that could improve conditions for students of color on our campus,” Bahur says.

He remembers one particularly heated meeting that focused on faculty hiring and some proposed changes to the faculty hiring handbook. There was a proposal to make the membership of faculty hiring committees ethnically and racially proportional to the population in Sacramento. It created quite a stir, and there were people for it and against it, he says.

“She spoke up in favor of it really passionately and gave context and reasons why it was important for our students to see themselves reflected in their professors,” Bahur says. “I thought it was a really courageous stance for a relatively new faculty member. Sometimes when professors are new they sort of take a backseat and don’t vocalize strong opinions that might not be popular. I was just impressed with that and the way she did it, with a lot of grace and convincing passion.”

Bahur says faculty members responded to Rodriguez favorably and positively.

“She had an ability to inspire people to rethink their positions and to be better, really — to sort of try to match her commitment and her passion,” he says. “You know, we are a collective as much as we’re individuals. We also are a collective body, and we do have the power and responsibility to inspire each other and to help each other. I think she took that really seriously.”

A model of inclusivity

Prior to teaching at City College, Rodriguez earned her bachelor’s in philosophy from San Jose State University and her doctorate in philosophy from University of Minnesota, according to her curriculum vitae. While earning her doctorate, she also taught philosophy at University of Minnesota in 2006 and at Minnesota State University from 2003-2007. She then taught philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (part of the City University of New York) from 2007-2014 before moving to Sacramento to teach at City College. Throughout her academic and professional career, Rodriguez gave a number of presentations on topics relating to diversity and inclusivity. She was in the middle of writing a book titled “The Ethics of Humor and Identity: Cultivating Empathy across Cultural Difference” at the time of her death.

Rodriguez brought her passion for equity to her work at City College. Ramirez says Rodriguez was critical to the STEM Equity & Success Initiative because she identified as a woman of color (half Puerto Rican and half Euro-American) and would share her experience with faculty members who made assumptions about who she was or about her experience.

“I always loved seeing that — when she would come out of left field and say, ‘I lived that student experience,’” he says.

Ramirez thinks Rodriguez provided a good example of how teachers can connect with students who may come from different racial or ethnic backgrounds.

“That’s what she brought. She modeled that for our program [and] for the other Euro-American participating staff. That’s what I think made her stand out. Sometimes our students don’t have the best experience with Euro-American teachers,” he says. “She’s an example that there’s potential everywhere. You don’t have to be Mexican-American [or] Latino to connect with students that don’t look like you.”

Elizabeth Forrester, a retired professor from the philosophy department who mentored Rodriguez when she began working at City College, says that Rodriguez brought critical insight to the philosophy department with her bicultural background.

Forrester describes Western philosophy as being all male and predominantly white and says that it can be a struggle to find philosophical figures of different backgrounds.

“We had some meetings that stood out in my mind about cultural relevance and how to make the classroom inclusive for all races and genders,” Forrester says. “She had some really good ideas because the other three of us — two white males and one white woman — we wanted to do it [and were] very happy and willing but needed some ideas.”

Forrester also says Rodriguez was well-versed in both Western and Eastern philosophies, due to her thorough education in Western philosophy and her Buddhist beliefs.

“We were very happy to get her,” Forrester says. “She just had everything we were looking for. She had some experience and really understood Western philosophy.”

Ramirez says that one idea Rodriguez introduced to her classes was the idea of a “healing circle,” something Ramirez had introduced to the STEM Equity & Success Initiative through the National Compadres Network. The healing circle is a framework the network uses that has facilitators begin conversations by asking “Who do you represent?”

“I provided some examples on how that was done,” he says. “She actually adopted that. She adopted that as part of all her classes and used that to connect with her students. She used that as a reminder for students and for professionals of why we do what we do.”

Rodriguez reminded her colleagues of being in tune with their mission, he says.

Student-focused teaching style

As an instructor in the STEM Equity & Success Initiative, Rodriguez knew that her students were not planning to become philosophers, according to DeMartini. Because of this, Rodriguez wanted her students to take what they learned in her class and use it to enrich their own lives — something that came across to her students.

“It was less about ‘You’ve got to memorize what Plato said’ and more about ‘What is Plato talking about here, and how can you learn from this and use it to benefit you?’” DeMartini says. “Anyone can just memorize Plato and take a Scantron test and forget about it two days later. They carried it with them.”

DeMartini says that many of Rodriguez’s students said that she transformed their lives.

“It’s a devastating loss for our college to lose a teacher that can have that kind of impact on our students and our future students,” she says. “It’s a loss for our college; it’s a loss for our community.”

When DeMartini asked students how their philosophy class with Rodriguez was going, she says they would respond that Rodriguez made the class fun and cared about their learning the material. Rodriguez cared more about her students’ understanding of the material than the grade that they received.

“I’ve heard her talk about her approach to grading,” DeMartini says. “It’s about the students — how they’re responding to the content, not about mastering it on some superficial level — which is totally inspiring.”

Timothy Quandt, an associate professor and department chair in the philosophy department, says that Rodriguez’s teaching style enabled her students to learn philosophy in a positive, unique way.

“Tanya brought a fresh style of teaching philosophy to our department by having the students blog instead of take tests, and by requiring each student to meet with her twice during the semester to discuss ideas and concepts from the class,” Quandt says. “By implementing these teaching styles the students were able to experience a form of learning philosophy that was unique and in most all cases welcomed.”

Rodriguez based her students’ grades upon their blogs and their discussions with her, according to DeMartini.

“She continually reminded us of the purpose of our jobs, which is not to test and grade and take points off, but to create a learning environment that empowers our students and transforms their lives,” DeMartini says.

A ‘spark of energy and joy’

Bahur describes Rodriguez’s dedication to her students as cariño, a Spanish word that he says often shows up in equity literature about teaching in diversity and equity. It means to show care and equity for students.

“We’re not just content delivery mechanisms,” he says. “Classrooms are a social context, and that kind of human interaction/relationship is important.”

DeMartini says that a number of Rodriguez’s students showed up to her memorial in August, even though they didn’t know her family or anyone else there.

“It was really sweet…” she says. “That’s when you know you had an impact on students — when they show up to your funeral and want to honor you in that way.”

DeMartini says that Rodriguez deeply loved what she did.

“She loved, loved, loved teaching. She loved her students, and she loved life,” DeMartini says. “I went to her memorial, and that was the thing people said. She was the most alive person a lot of us really know, which is one of the things that made this so incredibly devastating.”

DeMartini describes Rodriguez as being very active in life. She was an avid swimmer and mountain climber, according to the Sacramento Bee.

“There was this spark of energy and joy within her, and that’s what she brought to everything she did,” she says.

Forrester says Rodriguez lived life to the fullest and helped others to do so, too.

“She was very community-minded and very loving with her family and her roommates,” Forrester says. “She’s just a great person, and I just couldn’t believe what happened to her because she was vivacious and alive — and just to have that taken away, I can’t understand it.”

DeMartini says that she and Rodriguez got to know each other better after classes went remote.

“I got to know her so much more after we went online. I don’t know why,” she says. “I would always think, ‘I can’t wait until this pandemic is over, and we’re going to go and have beers.’ Obviously, we can’t. That sucks.”

Rodriguez was fun, funny, and always up for an adventure, according to DeMartini. She says Rodriguez was very centered, too, though.

“She had a really strong spiritual side, too, which I didn’t know about, but at her memorial, I learned she really embraced Buddhist philosophy and practices,” DeMartini says. “She was really interesting — that kind of juxtaposition. When I think of Buddhism, I think of quiet peace — and she was that — but she was also funny and alive and reverent.”

DeMartini says that Rodriguez was very passionate about living a meaningful life.

“She pursued life, and she wasn’t afraid of life. She wasn’t afraid of the big questions, and she loved that philosophy was a way to bring that introspection. That kind of introspection let her live her life to its fullest,” DeMartini says. “I will continue to be inspired by her the rest of my life. I think about her when I want to remind myself to not be afraid, and to not be afraid to deal with the big questions.”

City College has established an SCC Tanya Rodriguez Memorial Scholarship in Rodriguez’s memory. Checks may be made out to Los Rios Colleges Foundation with the memo “SCC Tanya Rodriguez Memorial Scholarship” and sent to:

Los Rios Colleges Foundation

1919 Spanos Court

Sacramento, CA 95825