“A long time ago… in a galaxy far, far away.” The familiar line in an opening crawl of text comes toward the audience set against a deep space background, soon moving down to reveal a planet and the first two starships locked together in combat, one towering over the other.

In the darkened living room, the front of the TV set glows, light flickering from it with every laser blast flashing on screen, barely illuminating each onlooker’s face. The screen entrances a watching family unit — a mother, a father and a 5-year-old boy named Patrick Crandley. He looks up, wide-eyed, taking in every part of the experience.

“Star Wars” lit young Crandley’s imagination on fire from an early age, guiding what would become a lifelong passion for creating models, from ships to trains to everything in between. From the physical world of models to the computer-generated world of digital 3D creations, Crandley ended up an industry professional and eventually landed a job at Sacramento City College as a graphic communication professor, where he now teaches those skills to others.

Like many great journeys, Crandley’s has a number of milestones, moments where the direction of his life shifted, pushing him ever closer to his final destination, and learning his own truth about what modeling means for him. One of his first milestones began not long after he first saw “Star Wars.”

“I grew up in a military family,” recalls Crandley, now 36, “and the base’s exchange (kind of like a Walmart) had kit models, paints and brushes that residents on the base could buy. I was captivated with the process and was completely enthralled with the idea of ‘building things.’”

A 7-year-old Pat Crandley glances across an aisle of plastic kit models lining one wall. He chooses his first kit, a B-17 Flying Fortress, eagerly taking it home and quickly removing the packaging to reveal a series of pieces attached to square plastic frames. Carefully, he pops out each piece. A wing. A cockpit. A tail section. Then he examines the instructions, analyzing how the pieces fit together. With lots of glue and a little patience, he assembles the kit. He delights in painting the exterior and applying decals.

Though he will later decide that the finished product isn’t very good, the result matters little in the end, nor does it take away from the fun of building the B-17 Flying Fortress. He glances with a smile, proud of himself for conquering this, the first of many plastic kit models to come.

Crandley sits comfortably at his teacher station toward the left front of a class of eager rows of students sitting at Mac work stations across a half-lit classroom. Drilling through the last of the roll, Crandley takes quick glances at the rows, noting hands or nodding as he remembers who he’s seen today, “Tyler is here. Simon, where’s Simon? I saw him. Isabelle.” Checking the classroom, he grimaces, “Negative on Isabelle.” Finishing up the roll, he exclaims, “Rock ‘n’ roll everyone!” as he moves to the center front of the classroom.

“Each frame is a painting. This is pushing the aesthetic of animation. Ten years ago, something like this would be impossible. I love it.” — Patrick Crandley

“I’m going to start off with what you guys don’t want us to do,” he says with a smile. “I’m going to show the [animated sequence homework] for last week. Part of being an animator is looking at the work at what others have done and using their successes and their failures as a guide — as a barometer for how to go on.”

Pat Crandley carefully observes a starship flying across the television screen. At 13 years old, he has seen the “Star Wars” trilogy many times and has carefully observed the detail work in each ship and vehicle model onscreen. Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), the model shop that created all of the effects of “Star Wars,” is the best in the business.

After the movie, he sits down at his latest model kit. Though his skills have vastly improved over the years, he knows he still has a long way to go before he’s of the ILM caliber. He glances at his fingers, noticing dried glue fragments peeling away, a direct result of finishing the model.

A commotion in the next room calls for his attention, and he steps into the living room to find his father home.

“What’s this?” Patrick wonders aloud as his father presents a clump of 1.44-inch floppy diskettes with the curious title, “Video Toaster.”

“You should check this out…. looks like fun,” his father says.

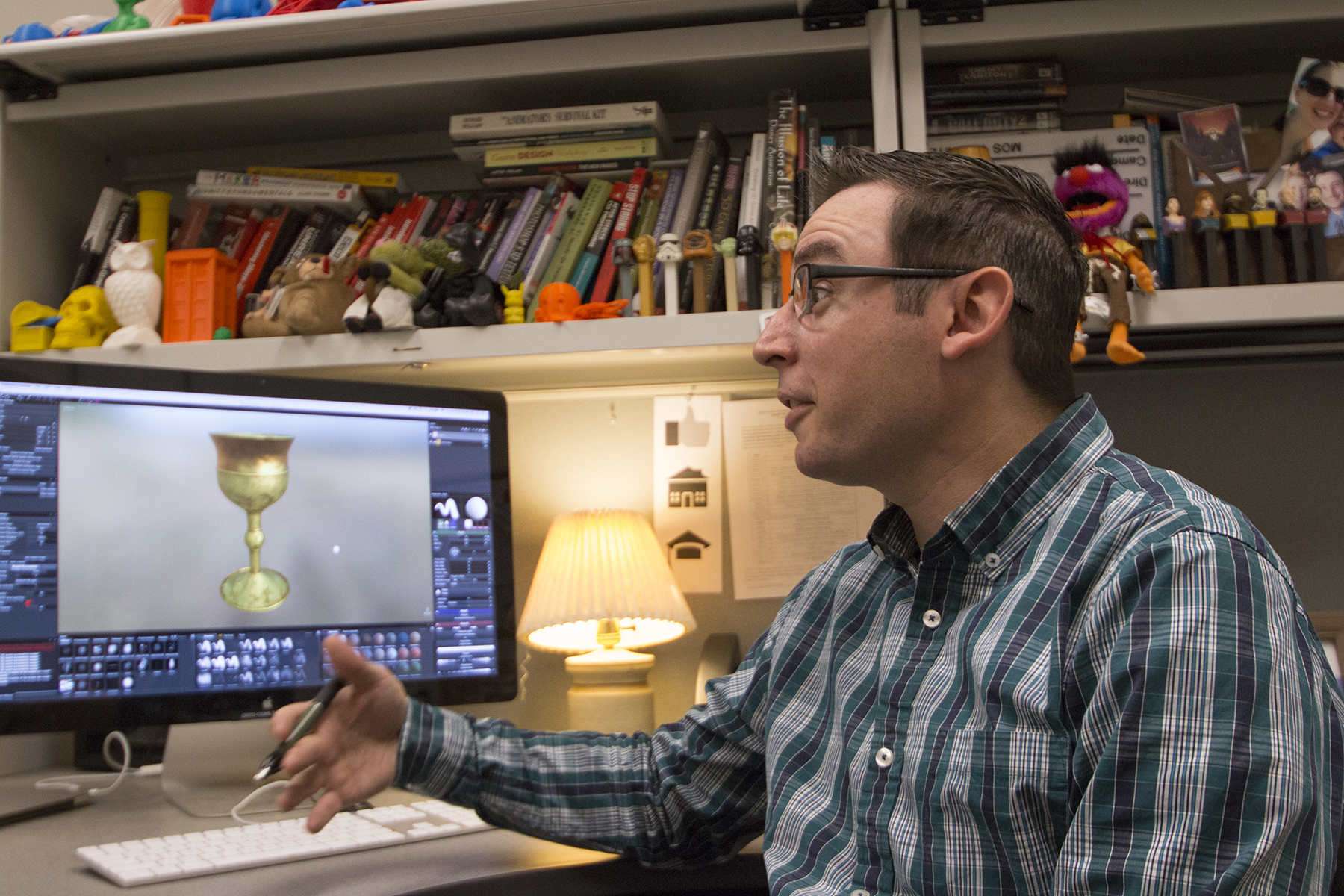

A moment later, Patrick sits down at the family Amiga computer, popping the disks in, one by one, installing every piece of software on them. A video editing suite. A digital 3D modeling program titled Lightwave 3D.

Intrigued by Lightwave, he loads up the program and begins fiddling with the controls. Through exploration, he discovers how to create a digital shape on screen, then rotate it, and manipulate its size, all in three dimensions. He fiddles around with the digital lights as they shine on the surface of the shape. Then he slices up the shape, alters its form.

“Rad,” Pat whispers.

Feeling his fingertips, he glances down at them, still encrusted with dried glue. Then he stares back at the screen, at his newly formed creation. In the computer, he can create whole worlds, limited only by his imagination, with no real world restrictions. This, he surmises, is the future.

In his animation class, Crandley calls out, “Someone brought this up, the Van Gogh…” As he talks, he pulls down the large screen from the ceiling and steps over to his teacher work station. With the click of a mouse, the light of the projector flares up, brightening the screen with a YouTube video trailer on pause. “… and, as you can see, it’s an animated film, which I think is absolutely rad.”

He clicks “play,” and the class watches the trailer of the film, a project by a group of artists who replicated famous paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, turning those images into a short animated film.

As the trailer finishes, the class ramps up in excitement, quieting only at Crandley’s words. “Something like that is herculean.”

The students murmur and agree, one calling out how nuts the post effects must be on a project of such magnitude.

“Each frame is a painting. This is pushing the aesthetic of animation,” Crandley declares. “Ten years ago, something like this would be impossible. I love it.”

Fierce clicking echoes across a small office in the middle of downtown San Francisco, the base of the studio, Wireframe Garage. No fancy adornments mark this place, just basic folding tables set up with several computers. Cables run everywhere with no regard for aesthetics. Artists work tirelessly on their parts of a grander project — completely computer-generated 3D animation recreating the Apollo 11 moon landing. The 20-year-old Crandley, a production assistant paying his dues, zips between tables, carrying various cups of coffee and delivering them to craving hands.

Crandley sits down at his table-bound computer and begins shuffling through folders with photographs, blueprints and schematics detailing all the parts that made up the Apollo 11 mission, including the Saturn 5 Rocket, the command service module, and the Apollo Lunar Module. After examining a photograph, he clicks on the computer in front of him, tagging a description of the image and where to find it. He then moves on to the next photograph.

Alex, Crandley’s immediate supervisor, steps into Crandley’s world of cataloging, which prompts Crandley to stop what he’s doing and scoot his chair around. “What’s up?”

“Pat, we know you’re interested in 3D modeling. How about you do a little bit of work for us?” Alex asks, a knowing smile on his face.

Crandley’s eyes light up.

“It’s nothing too big or exciting,” Alex adds, “but it’s a start.”

Soon after, Crandley scans a reference photograph. On screen, he recreates a bolt from the top of the command module. He relishes every part of the process, even for such a small piece of the whole. His first contribution to a professional project.

After eight years serving the industry in various capacities, with such wide-ranging projects as commercials, documentaries and episodic television, working with companies from MTV to Mike’s Hard Lemonade, Crandley lodged another milestone, once more altering the course of his life. While working as a senior editor and 3D modeler for Peppers TV in Sacramento, he noticed a teaching position open at City College.

Teaching, he says, felt like a natural direction for him. His grandfather taught. His father and mother did as well. It was his time to throw his hat in the ring, he decided, and see where it would take him.

At 28 years old, he became a full-time professor at City College teaching five classes each semester that range from introductory to advanced classes in both animation and game design programs. He also teaches at the Art Institute of Sacramento, plugging holes in their curriculum from time to time when needed. He refers to himself as a generalist, which he describes as highly adaptable to a variety of potential subjects along the lines of computer animation and computer modeling.

“He creates a very positive rapport with his students. And it shows in the high quality of 3D, animation and video game design work that they produce.” — Don Button

Back in the classroom, he tells his students, “The fastest way to get an artist to stop paying attention is to tell them their work sucks. I’m a big believer,” he pauses, “that it’s all about the little victories. Share the little victories, to keep people excited. We’re not going to start the day telling people what’s wrong with their animation; we’re going to look at the positives.”

Crandley clicks his mouse, and the first student–drawn animated walking sequence pops up on the big screen.

Jeff, the animator, calls out, “I’m very happy with the background.”

Crandley takes a moment to observe the sequence on loop. “Alright, what do you guys see in here?” He walks in front of the screen and notes that the figure’s arms might be distracting since the focus of the project are the legs.

“I do this often, where I’ll put my hand over the area I don’t want to see,” Crandley shows his hand clearly over his eye while he continues observing the looped sequence, “to focus on the important area. It’s a good start. It’s a really good start.”

“His name is George,” Jeff adds.

“This is a step in the right direction — no pun intended,” Crandley notes, laughing. “The center of mass is a little unbalanced.”

Crandley returns to his station. On his iMac, he breaks down the walking sequence second by second, all projected on the big screen as he zooms in, drawing over the screen to note areas of the animation, where the character’s hips don’t move up and down naturally. He returns to the front of the class and acts out a walking sequence, noting the position of his feet in relation to his hip and body movements. He makes exaggerated stomping motions to ensure every point hits clearly.

After going through all of the walking sequences, he says, “Good luck — may the force be with you.” He considers this for a moment, then corrects himself. “No, we’re not done today. That sounded like we were done — no.”

Laughing, he directs the students on the in-class lab assignment. “Let’s do grumpy. I like grumpy. Draw me a grumpy character. Body only, no faces. How are you going to pose our character to show grumpy?”

With that, he turns on some Beethoven on the iMac to set the mood.

In a huge, mostly empty office space with three desks, two of them empty, Crandley’s area is distinctly his. Beyond the papers filling his desk, two huge white wooden shelves to his right contain all manner of Star Wars models, various plastic kit models and a colorful array of 3D printed projects.

Sitting at his desk, Crandley states, “I can’t say that teaching inspires me — my students do. Every single day, my students come into the door with questions and experiences and a thirst to learn this art form and this pipeline.”

He goes on to mention that despite being such a big industry, computer graphics is a relatively small world, and access to education about it is often difficult, especially at the community college level.

“Usually this content is reserved for universities,” Crandley continues, “the four-year level, and definitely in the private world, where it’s tremendously expensive. So being able to offer this content here, at this level, in an accessible environment, is really, really quite amazing, one that I’m pretty passionate about.

“I feel that education should be free. I think my entire tenor here is access. Everyone should have the same opportunities to learn this material. We shouldn’t shut the doors to the animation graphics industry to folks just because they don’t have access to this information.”

“I was captivated with the process and was completely enthralled with the idea of ‘building things.’” — Patrick Crandley

If Crandley wasn’t teaching, he says he’d still be working in the production world, on computer animation and visual effects, while still having aspirations to work at Industrial Light and Magic.

“The genesis moment, the impetus of my entire career, like many people, was the original ‘Star Wars’ film,” Crandley says.

From that beginning, a world unfolded, from plastic kit models to computer animation, from professional visual effects work to teaching. He followed his dreams at every step, a person often in the right place at the right time, but also one who embraced every opportunity when it came. He didn’t make excuses, nor did he shy away from change. Instead, he plunged headfirst into the winds of computer animation and found a home at Sacramento City College.

According to Don Button, a fellow graphic communication professor at City College, Crandley’s students not only highly respect him, but they also love his classes.

“Pat brings so much energy and enthusiasm to his classroom,” Button observes. “He creates a very positive rapport with his students. And it shows in the high quality of 3D, animation and video game design work that they produce.”

This story was originally written by Jon Mercurio Knight and published in the spring 2016 issue of Mainline magazine.