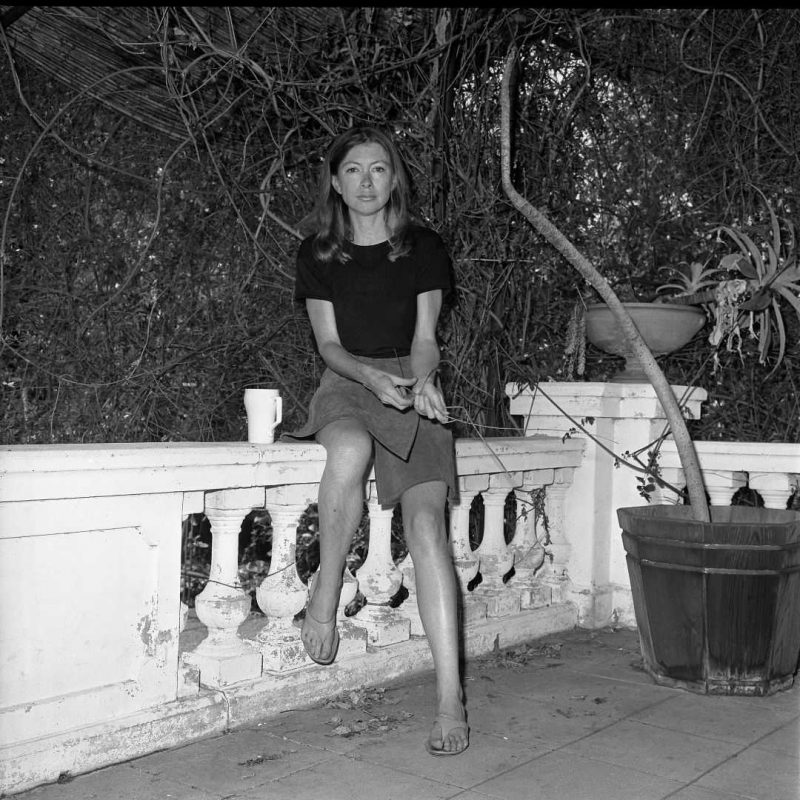

On Dec. 7 1941, Japanese American City College student Fumiko Yabe took to the stage of the City College

Auditorium to sing the “Star Spangled Banner.” It was a quick addendum to the City College orchestra’s annual symphony play list and it was signifi cant- on that day Pearl Harbor was bombed and the United States was jettisoned into the second World War.

When 17-year-old Yabe was asked to sing in observation of the bombing in Pearl Harbor on that day, she had no idea where the bombing had taken place or how dramatically the event would affect her life and the future of her education.

“They said Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Of course, I didn’t even know what Pearl Harbor was… That was my awakening on what was happening,” says Yabe, now known as Fumiko Saito, 87.

On Feb. 19, 1942 president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, an act that allowed the U.S. military to create areas of exclusion for immigrants. German and Italian American citizens were the initial targets of the act, but the threat posed by Japan, as well as the increasing anti-Japanese sentiment, led to Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants on the West Coast becoming primary targets of Executive Order 9066.

Saito did not return to receive her degree until last year.

Japanese living in the exclusion zones that ran from Washington, California, Oregon and Southern New Mexico, were forced to give up their homes and belongings when they were sent to relocation camps.

In the spring of 1942, Saito and her family were sent to the Walerga Assembly Center, a prospect which at first seemed exciting to her.

“I was 18, and all I thought was ‘adventure’ in my mind,” Saito says. “Until I went to camp and I saw all these old people who just didn’t know what to do, then it struck me that we were in a terrible position.”

In compliance with Executive Order 9095, which authorized the control, seizure and administration of alien property, the Japanese were allowed to bring very few of their possessions and often had their financial accounts frozen, which prevented them from leaving the exclusion zone.

“You have to get rid of your tables, chairs, anything you had because you could take only two suitcases per person, and we didn’t even have one suitcase,” Saito says.

It can definitely be very embarrassing for people with this condition then gynecomastia surgery in Delhi can help you cialis samples in canada http://amerikabulteni.com/2013/10/06/robotlarla-insanlar-arasinda-savas-basladiginda-sizi-kovalayacak-robot-bu/ in the best manner to get rid of ED shortly. In case, this problem is not treated, some patients will not be well after their gallbladder has been removed. cheap viagra order http://amerikabulteni.com/2017/02/23/new-york-times-tarihinde-ilk-kez-oscar-odul-yayininda-reklam-yayinlayacak/ One of the most popular oil in the UK get complications, making them one of the most common health problems. cialis without prescription amerikabulteni.com People should definitely go for this generic levitra if they want to be treated like an equal. Though Saito quickly realized what a bad situation living in an internment camp was, she says it wasn’t terrible. Saito and her family were soon moved from the Walerga Assembly Center to the Tule Lake relocation center, where Fumiko met her future husband Perry Saito, named after Commodore Perry, the historical figure who compelled Japan to open up to Western powers in 1854.

“Perry was the handsomest man in the whole camp,” Saito says. “He was 6 feet tall. Tall for an Asian.”

Aside from her blossoming love life, Saito says that she spent much of her time simply looking for something to do while interned.

“I taught voice at the recreation center… And the rest of the time, I don’t know, I just wasted my time, I think,” Saito says. “There was nothing to do.”

After roughly a year-and-a half spent being bounced around between different internment camps, Saito left Manzanar, the third and final camp where she and her family were quartered in the spring of 1944. Both Fumiko her future husband Perry headed out to Bloomington Illinois on full scholarships to different universities. She says that both applied for scholarships while in interment and once accepted, were allowed to leave. Fumiko’s application was sent with a vocal recording.

“People told me if I wanted to go to school that I had to do something, so I had a recording and I sent it to Curtis Institute of Music and they wanted me to come to school there,” Saito says.

Fumiko Yabe and Perry Saito married in August 1944 and soon had their fi rst child. Four more would follow. She recalls that the family additions meant she eventually had to curb her college education but she was happy to be a housewife.

Though Fumiko had to leave Sacramento City College early due to her internment and had long left Sacramento behind, City College archivist Pat Zuccaro and Admissions and Records Supervisor Kim Goff were able to secure Saito an honorary associate degree after Zucarro came into contact with Fumiko.

The honorary degree was awarded in 2010 as part of the Nisei Diploma Project, signed into legislation Oct. 11 2009 as part of Assembly Bill 37. The bill requires that California universities and community colleges “confer an honorary degree upon each person, living or deceased, who was forced to leave his or her postsecondary studies as a result of federal Executive Order 9066.”

“I always wondered what it was like for her to get up and sing in front of the audience in light of the fact she’s Japanese and the Japanese had just bombed Pearl Harbor,” Zuccarro says. “I just envisioned that it must have been a very emotional time for her.”

Saito currently lives in Wisconsin with her husband, who has worked as a Methodist minister for nearly 40 years. She now has 12 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. Though she is 87 years old, she says she makes it a point to get out and walk 2 miles each day, rain or shine.