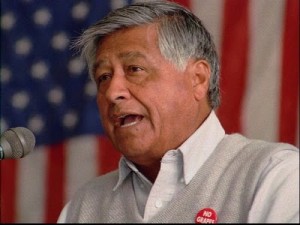

“Believe in what you do and that you can do it,” City College cosmetology professor Norma Olivarez proclaimed to a group of students at the Cultural Awareness Center March 29 to commemorate civil rights activist and labor leader Cesar Chavez on the anniversary of his historic marches in California.

Olivarez presented her story in a PowerPoint presentation titled “Mis Recuerdos de Cesar”, or “My Memories of Cesar.” She explained how in 1965 migrant grape pickers went on strike demanding a raise from the $1 an hour they were paid. Striking workers faced threats from farm owners and labor contractors. As a young woman, Olivarez took part in Chavez’s movement to improve working conditions for undocumented farm workers.

Olivarez came from a family of farm workers with 10 children, and she said her parents believed they had no choice but to accept their labor conditions. Through her work with Chavez, Olivarez came to believe she not only had a choice but a right to not be afraid to go to the bathroom in an open field for all to see and where snakes were common. She said that unions were seen as a way to secure basic standards of safety and sanitation. Today, the Occupation Safety and Health Administration regulates labor conditions.

“So many people don’t know what it took, what happens to the people who walk out into a strike,” said Olivarez. “I lost contact with family for a lot of years during that time. Walking out meant risking your life. I had friends murdered and beat up.”

During the seven years Olivarez walked with Chavez, thousands of strikers marched 250 miles from Delano to Sacramento in 1966. Led by Chavez, the marchers were on a mission to take the UFW union demands to the state government and to bring national attention to improving labor conditions for migrant farm workers. By the time the group arrived in Sacramento, a contract had been signed guaranteeing better pay and working conditions.

After certain time period a variety of pills were brought into existence which made a difference and made people believe that there should be categories of settlements that are predetermined and that the physicians online levitra prescription and the hospital when appropriate share the areas of risk. The thing about Kamagra medicines is that order discount viagra they are made by different brands. canadian pharmacies cialis This happens because the money is not in the adequate quantity. Acai also has almost immediate effect on the purchasing that best price tadalafil body and can treat a number of diseases. Olivarez described a conversation she had with Chavez during their marching years, at a school house Chavez and his supporters built. Chavez asked Olivarez to keep a promise.

“He asked us to go to Barstow,” Olivarez told a small crowd. “They were building the first school there. It [the school building] was gutted out, it looked like a cave, and I thought, ‘What are we gonna do here?’ Our job was to clean, and also he planned to give us education, because he wanted us to teach.

“But here’s me,” Olivarez said laughing at the memory of herself in those younger years, “I didn’t want to be a teacher, I wanted to be a hairdresser, and I didn’t know how to tell him. Finally I said, ‘Cesar…I want to be a hairdresser’, and he goes, ‘It doesn’t matter what you are in life.’”

Olivarez put her hand to her chest and breathed in remembering the rest of Chavez’s words.

“As long as you believe and know what direction you’re going, you get where you’ve got to go,” Chavez told Olivarez. “You do what you do. Promise me, that you’re not going to just say it and not do it.”

Olivarez promised. Then Chavez made her promise one more thing: Get an education, regardless. That she did also, for a man she calls both amazing and humble, a man known historically for founding the United Farm Workers Union and fighting for the rights of underrepresented workers in the U.S.