Teri Barth | Contributing Writer

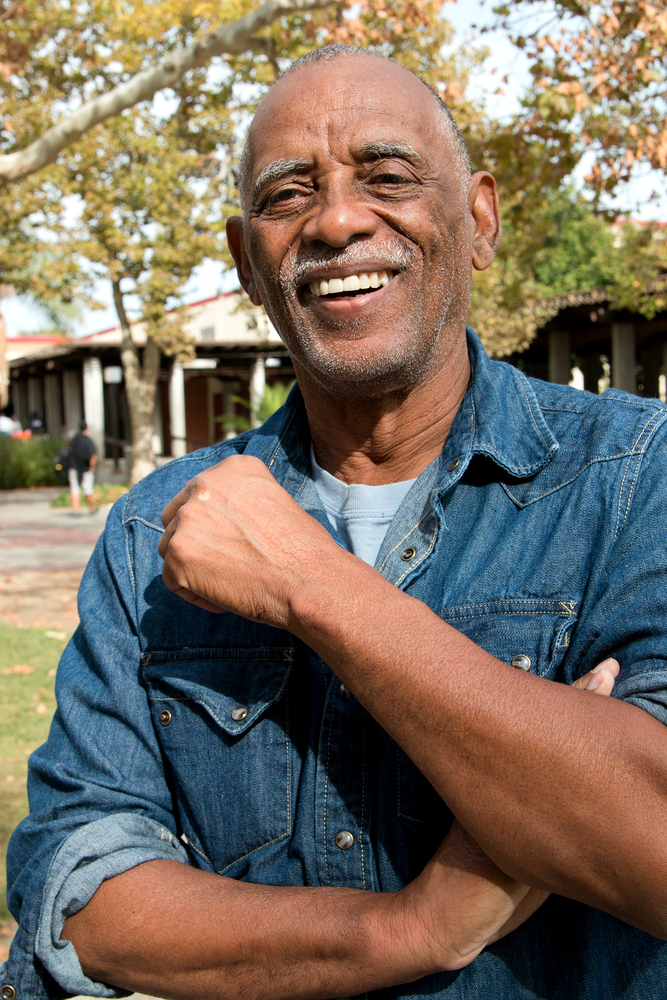

Fred Foote recalls his historic role in the Civil Rights movement

The late 1960s. The women’s rights movement was gaining momentum, the anti-Vietnam War movement had firmly grasped people’s attention, and the civil rights movement took over the streets. Rallies — most peaceful, some

not — and other soapbox platforms lasted seemingly for days. America’s black men and women had spoken up, and among them was a catalyst for change on campus.

More than 45 years later, sitting on a familiar concrete bench under an old tree on the City College quad, that catalyst recalled those days.

“It was just a huge, tumultuous, building, never-ending, thriving, riving kind of activity, and it just kind of blew you [away],” says 71-year-old current and former City College student Fred Foote. “This campus was alive with activity. It was so different, even though the structures were the same.” Raising his arm, he points to the Learning Resource Center, which replaced the old library. “Except for that one over there.”

Born Frederick K. Foote, Jr. in 1943, Fred has lived most of his years within 5 miles of City College. It was in the south area of Sacramento and on campus that Fred fought for the civil rights of minorities.

As a young African American City College student, Fred co-founded the Sacramento City College Black Student Union. With Fred as its vice president, the BSU played a key role in bringing ethnic studies courses and instructors to campus and in forming the Oak Park Afro-American School of Thought. Fred also co-founded the Third World Liberation Front and the Sacramento Area Black Caucus. His accomplishments not forgotten, Fred’s smiling eyes cannot hide his pride at being a cornerstone of the community.

“I moved to Sacramento in June of 1970,” says David Covin, a Sacramento State professor of government and ethic studies and co-founder of the SABC. “One of the first things Grantland Johnson, then one of the BSU leaders at Sac State, told me, was, ‘You’ve got to meet Fred Foote.’ By the time I met Fred, in 1972, he was a living legend.”

A McClatchy High School graduate, Fred remembers his days of running track and field with the City College Panthers when the Vietnam War was not mentioned or taught. Fred considered it a “worthless piece of crap of a war” that robbed students of their college experience and silenced the campus.

After the war began, Fred says the stage in the quad that once boasted performances during student hour was suddenly deserted. Students shifted their interests to something more intense, gathering solemnly at cafe tables listening to war updates from faceless voices on transistor radios.

“It was a whole different era,” says Fred. “It wasn’t an abstract about whether [the war] was good or bad. Students were in the streets because the war actually concerned us. People were being drafted, and a lot of us were really convinced that this was going to be the end of the world.”

Fred says he and others noticed an unfair draft ratio of black to white men, which indicated that his dark skin meant he could receive draft papers at any moment. But Fred did not wait for his to come, instead voluntarily enlisting in the United States Air Force.

“I decided it was time to go into the service because the service was probably the safest place,” says Fred. “You don’t have to be a historian to figure out that mostly civilians are the ones that get killed in our recent wars. So [my reason for enlisting] wasn’t patriotism or glory. I just thought that I would be safer there.”

Fred wasn’t sent to Vietnam, though. He made it as far as Canada, where he did a volunteer stint as a military radio disc jockey. Fred returned to Sacramento in October 1966 with his appreciation for the civil rights movement still intact. Other ex-GIs like Fred who had returned to school at City College shared similar disenchantment with the state of affairs on campus. They wanted to abolish racism in education.

“There were no ethnic studies [courses],” says Fred. “Not many people saw there was a need for them. [The college] administration, they thought everything was fine, as good as the world could be made.”

In 1967, other colleges had effectively formed student unions and had succeeded in forcing change on their campuses. Fred and his ex-GI comrades decided that they could do the same, and in February 1967, they invited as many African American students as possible to what became the first Sacramento City College Black Student Union meeting.

Expecting maybe 10 students, Fred recalls that he and his fellow BSU founders were astounded when nearly 40 students arrived for the meeting. “We figured we would get a few people, but every black person on campus showed up,” says Fred. “We were just blown away the eagerness of people to participate. We got people to come who were really interested in doing something, people who were interested in not just being another club but in being a political organization.”

Among those who attended that first meeting, Fred was eager to meet one in particular. Kinnie Hicks had been on Fred’s mind since he first saw her handing out programs at an off -campus event at Sacramento State.

According to Fred, Kinnie — who prefers to go by her middle name, Ruth — was beautiful and outspoken, a combination he liked. When he saw Ruth at the BSU meeting, Fred made a point to meet her. In 1968 the two married, and Ruth says their 46-year long marriage remains strong.

“I’ve been extraordinarily blessed and fortunate to have a wonderful husband. Extraordinarily blessed,” says Ruth. “He’s a really a good guy. He’s what he seems to be, and I’ve been fortunate.”

Ruth agrees that the first BSU meeting was a success because people of color united on campus. “What I liked about [the BSU] was that black people were coming together with a consciousness about their situations, whether it was with the school or the police department or with whatever,” says Ruth. “But we were coming together, and that

meant a lot to me.”

The BSU originally intended to pursue equality for African American students but soon decided to welcome all students regardless of race.

“One of the first meetings, a brother brought his girlfriend who was white there, Margaret,” says Fred. “[The members] immediately wanted to kick her out, but we said they couldn’t. We didn’t want to replicate the same kind of discrimination we had suffered.”

The BSU gained strength and presented 10 specific issues to the college administrators, including a demand for ethnic studies offerings and an educational outreach center in the community of Oak Park.

“The air was electric,” says Fred. “The moment you got [on campus] it was a hubbub of activity. It was extremely busy and very stressful because you never knew what the next adventure was going to bring or where the next shoe was going to drop.”

The shoe did drop — the college administration rejected the BSU’s demands. In turn, the BSU made sure administrators understood that the BSU likewise rejected their rejection.

“We didn’t have to be rational,” says Fred. “[The administration] didn’t think we were [rational] anyway, so [we used that] inherent racism to get what we want. I don’t know if we wanted their respect or their fear. What we wanted was concrete progress. It was very pragmatic.”

The BSU scheduled marches, encouraged students to strike and rallied across campus. The college’s black students held handmade signs and shouted through bullhorns. Rally after rally, the BSU made headlines. Soon, the BSU learned to manipulate the press.

“We realized the press [were there] for just a couple of words,” say Fred. “They wanted to hear somebody say something about violence or racism, or something like that. They never wanted to stay long though. We would time things so we could get a couple of speakers on that would give them their key words but in a different context. We [BSU members] would still get our message across, but at the same time they would get their sound bites.”

Their message, in fact, was getting across. The BSU’s demand for ethnic studies offerings at City College changed the education of black students. But change, Fred points out, is a tricky thing. “You have aspirations for one thing to happen and then something happens, [but] it’s not exactly what you expect,” says Fred.

“We were disenchanted with some of the ethnic studies classes because they were just classes talking about, ‘I’m black and this is how I feel,’ and [students] could get a grade for being black,” he explained. “We thought we could get people who wanted to seriously examine the issues and try to find solutions, not just people who were promoting themselves or saying, ‘Oh, god, it’s horrible being black,’ or saying, ‘I’m proud to be black.’”

Finally, college President Sam Kipp met the BSU’s demand for off-campus space for The Oak Park School of Afro-American Thought. But when Fred and his peers couldn’t locate the space, they asked a janitor if he could point them in the right direction. Instead, the janitor took them to it.

Fred recalls that he reached out and grabbed hold of the doorknob, turned it and, as the door opened, their hearts sank.

“It was like a broom closet,” says Fred. “We were really disappointed. It was literally not much bigger than a broom closet. The president had given his word. He says we’d have space, but it was insufficient and really not at all what he had promised.”

The next morning BSU members decided to stage a sit-in, cramming into the president’s office until not one more person could fit. But they didn’t stop there.

“[The space] was totally unacceptable, and [the president] wasn’t acting in good faith,” says Fred. “So we took over the administration building. We just set people in the administration building throughout lunchtime, and they sang songs and such until everybody else just faded away. The next day we held a rally.”

During the rally, Fred says the BSU received news that Los Rios Community College District had met the demand for adequate space. Portable trailers were in transit from San Jose, each designated as official meeting space for the Oak Park School of Afro-American Thought. Fred and the other BSU members were ecstatic.

“It was perfect for us,” says Fred, his eyes beaming. “It was in the heart of the community that we wanted to be in. It was spacious and something we could take care of. We loved it very much.”

Still, when in was time to say goodbye to the college, Ruth says it was bittersweet. “The consciousness fell to the wayside, but we went on and we formed the Sacramento Area Black Caucus. Fred and I were founding members, so we just transitioned from that level to an adult level.”

In 2004 Fred returned to City College as a professor of social sciences. There, his accomplishments came full circle, when, at the request of the Los Rios Community College District, Fred agreed to teach Ethnic Studies. Drawing from his own college experience, Fred says he approached teaching differently than other professors. He told his

students to question authority and not to let fear stop them from changing the game so it runs their way.

“We were a catalyst for change,” says Fred of his first stint as a student. “It was all of us together. No one of us could ever have accomplished it. I felt that I was part of a community of change, and that felt pretty good.”

Editor’s Note: this article first appeared on December 8, 2014 in the fall 2014 issue of Mainline magazine.