By Rose Vega and Ben Irwin

Re-Emerging Scholars

Formerly incarcerated students walk a new path at City College

Photo by Sara Nevis

Three students at Sacramento City College aspiring to futures in public service—a high school counselor, child development professional and an entrepreneurial Child Protective Services case advocate—share a common past: They’ve all been formerly incarcerated.

They also share a common future: They’re actively working to create and live their visions of successful lives.

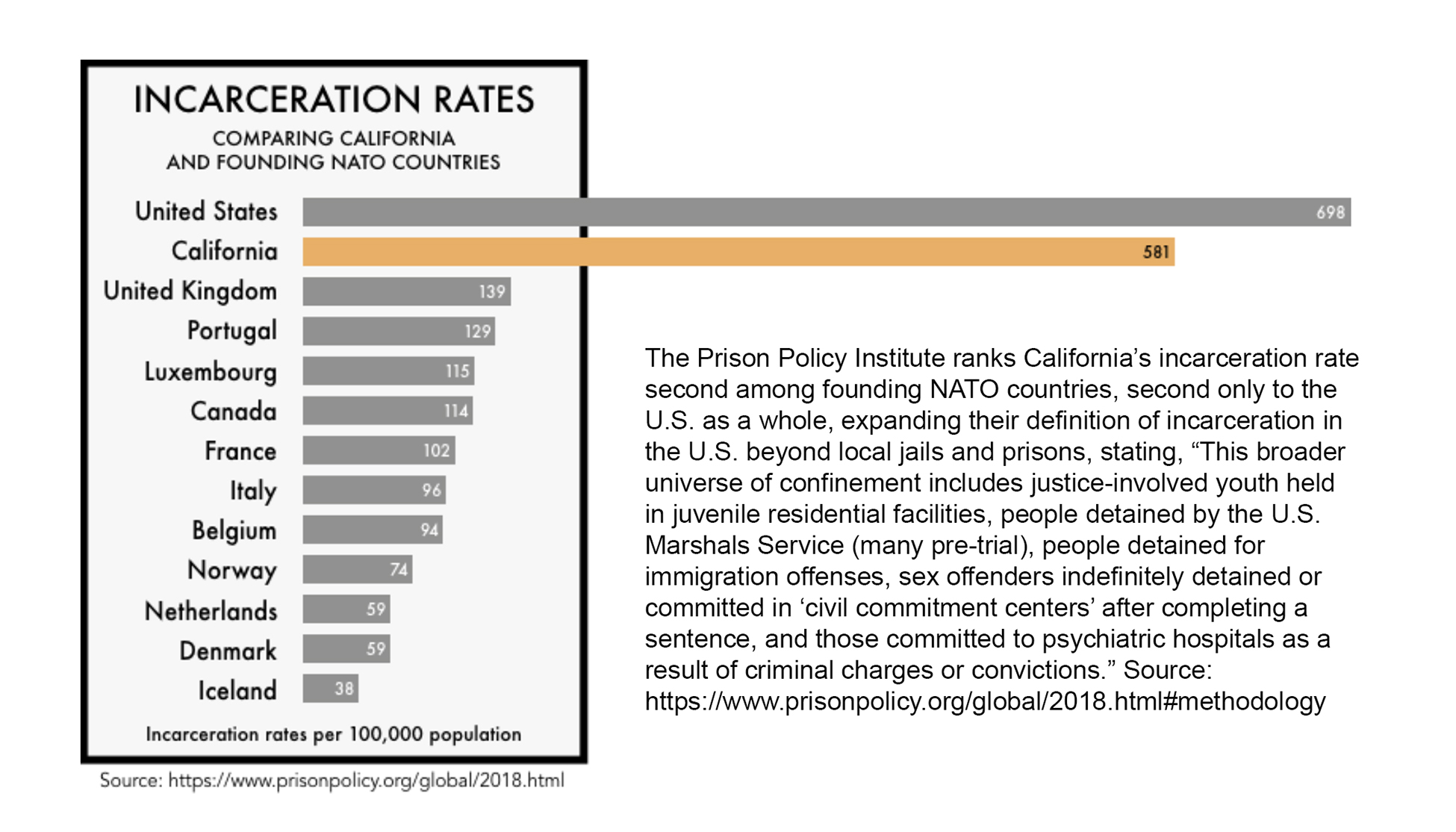

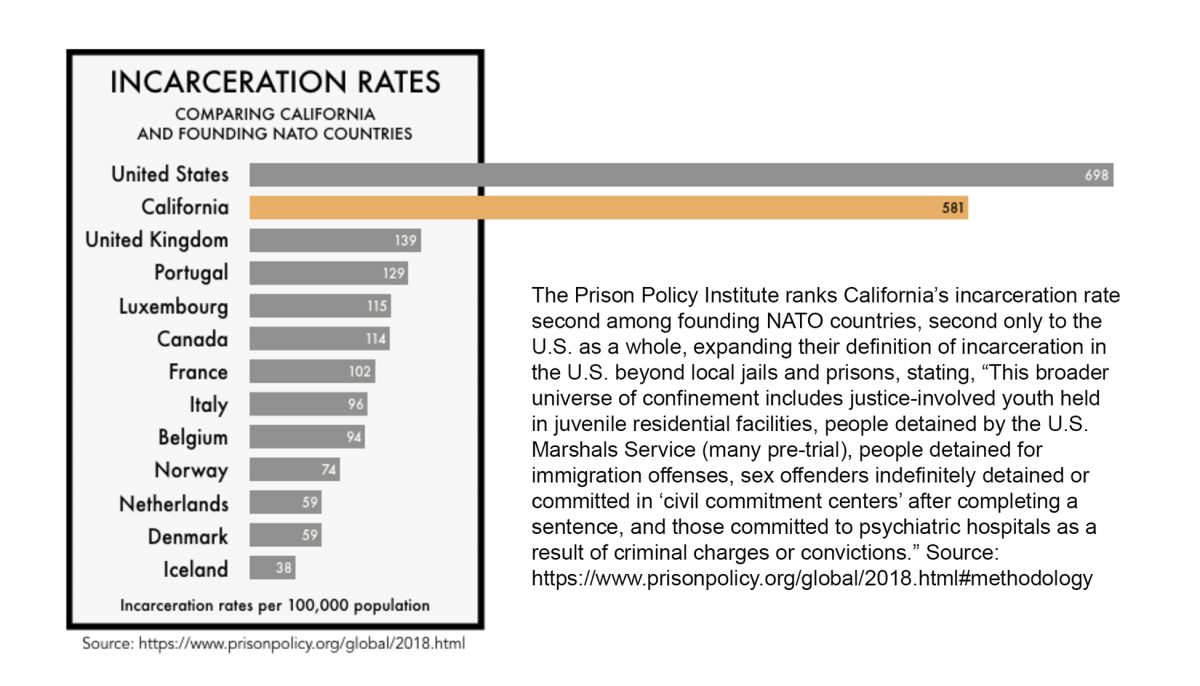

Mass incarceration is a national issue. While California has been touted in recent years for its work to end mass incarceration through legislation—realignment, revision of the “three strikes rule,” reducing penalties associated with nonviolent crimes and court-ordered prison population reduction—the Prison Policy Institute’s 2018 numbers on incarceration rates speak for themselves.

“The mass incarceration issue here in the state and across our nation is having this insane impact on our communities”

—Nich Miller, Re-Emerging Scholars co-founder and City College sociology professor

California recidivism rates—the rate at which criminals reoffend—have historically been among the highest in the United States, according to a June 2019 report from the Public Policy Institute of California.

The Re-Emerging Scholars program at City College is devoted to helping break the cycle of recidivism and institutionalization for formerly incarcerated individuals. It is in this program where these three students are redefining their identities, taking control of their lives and helping others.

Courtney Foston grew up with her parents in Carmichael before moving to Santa Cruz when she was 19 years old.

“I grew up in a middle class family. I didn’t grow up in a gang or anything like that,” Foston said. “Where I ended up—that’s all on me.”

Foston spent the entirety of her 20s in and out of incarceration for various criminal and drug offenses.

“I had no ambition to do anything,” Foston said. “I had never really felt a part of anything enough for it to be something that I was passionate about other than acting, and that all fell off when I started using drugs.”

A methamphetamine user, Foston said her life spiraled out of control when she watched her boyfriend and father of her young son overdose on heroin and die in her arms. She said she turned to heroin shortly after.

“When life happens that fast it’s so surreal,” Foston said of her boyfriend’s overdose. “Everything for me changed after that. Everything—it had to.”

Foston said her son also put things into perspective.

“That’s when I was like, ‘OK, you know what? I can’t do this anymore. This has to stop because I’m gonna end up like [her boyfriend]. My kid is gonna end up with no parents and just memories of us, and I can’t do that.”

After her boyfriend’s death, Foston said she “was on a mission to not feel anything” when she had to do an eight-month jail sentence at Santa Cruz County Jail.

Foston explained that after someone starts getting arrested frequently, the second the cuffs are on, “You’re in jail mode. You’re incarcerated.”

The social structure in jail can be addictive, said Foston, and she quickly adapted to it.

“It sucks, but when you don’t see yourself going anywhere else, then it’s kind of like, ‘Well, I’m gonna make sure that when I’m in here that I’m comfortable, and I’m gonna make the best of it because it’s gonna keep happening.’”

Foston said that maintaining that facade of no emotion and always being tough was hard to break. That proved to be a struggle when she was grieving the loss of her boyfriend.

“I was in there when I was finally able to grieve because they made me, and so crying in there was hard,” Foston said. “You don’t want to be judged, but at the same time I had to feel what I was feeling to get it out, or it was going to eat me alive. That was the hardest time I’ve done.”

For Foston, incarceration was defined by dominance. She felt that for women it wasn’t about race but drugs and fighting.

“How you dominate is you come in with drugs, which puts you on the top of everyone’s list,” Foston said, “or you have to fight. You have to fight for your spot on top, or you just have to know enough people in there, and if you don’t, then you better get to know people, and you need to know your place.”

Foston said that every time she went to jail, she would become less and less emotional, which helped her to not feel guilty about committing a crime.

“It gets easier the more you turn off those emotions to get through,” Foston explained. “It comes to a point where you’re so dope sick that you don’t worry about anybody else and how they’ll feel.”

Foston added that every time she got arrested and sent to jail, she’d learn more and more from the other inmates.

“I’d get locked up. I’d go on my run when I got out. I’d get locked up. Learn a little more from whoever was still doing time in there, then come out and better my game,” Foston said.

During the eight-month sentence in county jail after the death of her boyfriend, Foston was transferred to Blaine Street Facility, a lockdown work program within the Santa Cruz County Jail, where she said her life changed for the better.

“I went to a special unit where you’re given milestones for completing courses,” Foston said. “You get a certain amount of time off your sentence. I did a bunch of milestone courses while I was there.”

Foston said she appreciated the amenities at the Blaine Street Facility—TVs, couches, nicer beds and the freedom to do one’s own laundry.

“It’s just different,” Foston said. “Made you want to stay.”

Foston said there were good parts and bad parts from her experience with incarceration.

“I learned to pay attention to my surroundings. Even though I was using it for evil before, now I can recognize it in other people,” Foston said. “When you’re locked up, all the faulty people are inside, and you can call them out for what they are. You can’t do that out here.”

Still, Foston said, she finds it tough to break away from the institutionalized mindset.

“You become very used to things working a certain way in a certain order.” Foston said. “Then when you get out and get all these other options, it’s scary. I didn’t even know what kind of food I liked. I didn’t eat for the first week—there were too many options. I wanted to go use so I could go back in. That’s how that cycle builds.”

Foston is one of about 150 people who’ve come to City College in hopes of turning a new leaf, where City College sociology professors Nich Miller and Shane Logan are actively making a difference on the ground level, helping formerly incarcerated students break the cycle through the Re-Emerging Scholars program.

Logan said the concept of Re-Emerging Scholars came in late 2016 after a sociology club field trip to Project Ascend, a re-entry nonprofit.

“I did a presentation there on the importance of education in recidivism reduction programs, and a lot of their clients were very interested in becoming students,” Logan said. “I ended up signing up about a dozen students that took two classes with me.”

Logan recalled the front row of those classes lit up with glowing and beeping ankle monitors.

“These were hands down some of the most engaged and enthusiastic students we ever had,” Logan said. “Any additional optional lecture I had in my classes, those were the only students out of the entire class that would actually show up to those additional types of things. Their enthusiasm was incredibly high, but their success rate was not.”

Logan and Miller, frustrated with the gap between enthusiasm and success, began to troubleshoot the barriers to success for these students.

“A lot of those students were dealing with housing instability, a lack of support on campus, not having an advocate for them in between them and their probation and parole officers,” Logan said. “Nich and I talked about how we could, instead of being part of the problem, be part of the solution—to contribute to the identity transformation that they so desperately wanted.”

Logan said the sociology club soon transformed into the Re-Emerging Scholars club, which evolved into the multifaceted program it is today.

“We’ve got a full cohort-based program,” Logan said. “We plug students in to a selection of GE classes, hand selected by us that we feel are the lead dominoes that can help make them more successful in both their personal and academic lives.”

Among the selections are accelerated classes in classes in English writing and personal finance.

“As they’re getting these financial aid checks, it will help them budget so they aren’t blowing their entire financial aid in the first couple months and then having to live off of Top Ramen or experience more housing insecurity in the future,” Logan said.

The next step in Re-Emerging Scholars is the internship program, said Miller, where he coordinates an internship within Re-Emerging Scholars as a mentor to new members, or an externship with a partner organization.

“So much of Re-Emerging Scholars is about identity transformation,” Miller said. “You see the apprehension, the disbelief, the worry and the fear in their eyes as they’re signing up for classes. And the interns are saying, ‘I know what the feeling was like, I know the doubts you’re having, but you’ll be in my shoes six months from now.’”

Foston was referred to Re-Emerging Scholars by her mother, who works with a local probation program. She now co-facilitates the sobriety society club—an arm of the Re-Emerging Scholars program—on Tuesdays and serves as a mentor to multiple new students.

“I get to help other people the way [Re-Emerging Scholars] helped me,” Foston said. “I’m not a positive person—that’s because of incarceration, because of the lifestyle I lived. I don’t trust anybody. Being put in this leadership position, my mentees would never guess that. I am so positive with them, and I make sure to build them up and let them know what they are accomplishing is good and they’re moving in the right direction. All of them are doing great.”

Foston’s positive attitude with her mentees has given way to new revelations for her own mindset.

“That helps me, to learn that, ‘OK, you can trust people,’” Foston said. “‘Not everyone is going to try to put you in jail or call CPS on you. Just trust.’”

Foston, Miller and Logan all said they understand the importance of timeliness in bringing in new members fresh out of incarceration. Miller said the program has found success thanks to their relationships with local parole and probation programs, and the hard work and dedication of their student interns.

“They provide us referrals of people who have recently been released, and we have our student scholar interns reach out immediately to get folks to campus, to provide a model and example of what their next move in life is going to be,” said Miller. “Part of this is immediately matching new students with peer mentors who have been trained to think about the cycle institutional mindset, because they all understand it, and they are there checking in once a week at least in a deep and meaningful way, and then a couple times a week to catch any worries, fears and challenges that are happening.”

Logan said early intervention means incorporating new students into Re-Emerging Scholars regardless of how the timing of their release lines up with the academic calendar.

“The recidivism rate is highest in the initial months upon release.” Logan said. “Early intervention is a powerful tool we have.”

Kenny Nammavongsa, 23, is pursuing a career to be a high school counselor. But six months ago his life looked different. At that point Nammavongsa had spent a little over four years incarcerated.

While Nammavongsa was incarcerated, a friend asked him what he wanted to do when he got out.

“I told him I wanted to go to school,” said Nammavongsa. “I didn’t know specifically what I was going to school for.”

His friend had received a letter through the mail about Re-Emerging Scholars and told Nammavongsa about it. When he went to check out City College campus, he asked about the program and walked into the office.

“The environment was so welcoming,” said Nammavongsa. “That was the first day I ever stepped into the office, and ever since I never turned back.”

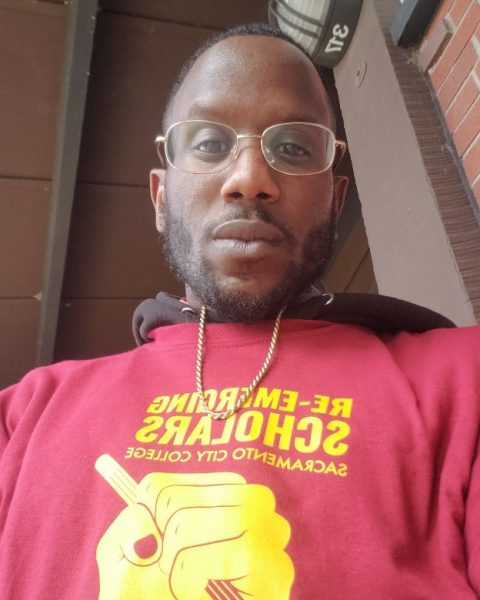

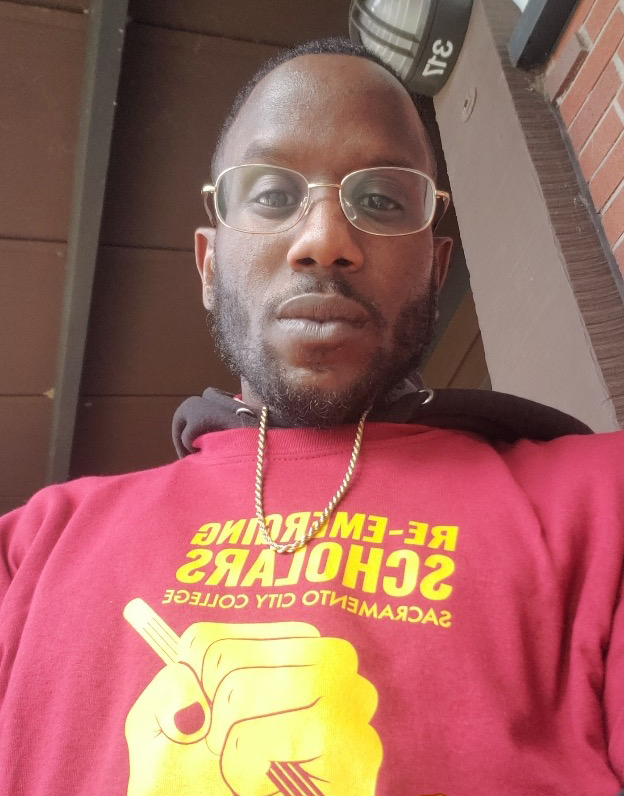

Like Nammavongsa, sociology major Julius Collins learned about Re-Emerging Scholars through a group of friends that he saw at an Anti-Recidivism Coalition meeting.

“I was actually signed up at ARC, but I saw these guys, and they were talking about the program at Sac City and the Re-Emerging Scholars,” said Collins. “That was enough for me. Just to see those people came from where I came from—prison—to see they were here supporting each other was enough.”

According to Nammavongsa, one of the great things about the program is its variety of mentors, because the mentors have experienced what a lot of other students have been through.

“That’s what’s so good about a variety of mentors in that program—because every one of them is different, and you’re gonna find the mentor that works for you,” said Nammavongsa.

Collins is one of those mentors and has been since the start of his second semester. While mentoring is new for him, it has allowed him to connect with people he knew while incarcerated in a more positive light.

“This is a great opportunity for me. Some of the outreach programs that we do I am directly involved in seeing people from parole—people that I have seen in prison over the years,” Collins said. “They are seeing me now like, ‘You’re not back?’ ‘Nah, I’m working with the school and mentoring now. I’m trying to make a way for us.’ I think it is encouraging for them and gives them hope in a way to see that we don’t have to be the same way. We don’t have to be stuck in that institutionalized framework of thinking.”

Logan stressed the importance of helping students see their past not as a liability but an asset. He recalled a re-emerging scholar from the early days of the program whose last year of formal education was seventh grade before he spent the next 20 years in and out of prison involved with the Norteños gang.

“During those 20 years he had been treated like an animal and a number,” Logan said. “His role within that gang structure was to educate and indoctrinate new recruits. He’s now applying to grad school looking to be a professor. Those same skills he was using in his gang network are actually powerful tools that he can use to educate students in a prosocial way.”

Miller explained why formerly incarcerated student mentors and interns are the heart of the program.

“They have an experience that we don’t have,” said Miller. “That’s an asset for them to really be immediate and powerful contributors to our community immediately upon release, where they can communicate more effectively than we possibly could with many of the folks that are re-emerging into society.”

While enrolled in Re-Emerging Scholars, Foston has been living with her mother in Carmichael. She said her son was living there for over a year while she was incarcerated, and she did not want to uproot him when she got out.

“I commute, and it….” Foston paused to collect her thoughts. “It’s working for now.”

Foston said she’s hoping to find a place of her own, but despite the paycheck from her internship with Re-Emerging Scholars, there are still significant barriers.

“I don’t have any credit,” Foston said. “Anything outside of Del Paso Heights or some other ghetto, they want two lines of credit, and this certain credit score, so I’m like, ‘OK, I’ve got to start building that stuff up now.’”

Miller and Logan said that they have been making a lot of efforts to expand the program, with their eyes set on housing.

“The goal that we have is to work with community partners and with the Legislature to get housing specifically for Re-Emerging Scholars and for re-entry,” said Miller, “because one of the biggest issues that re-entry into a population faces is housing. Having stable access to employment and affordable housing along with higher education are key to the long-term stability and success of re-entry intiativeatives in this state.”

Housing most likely wouldn’t be located on campus due City College’s landlocked status, according to Logan, but he and Miller have begun initial conversations with housing community developments with Re-Emerging Scholars in mind.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the college’s closure as of mid-March, the Re-Emerging Scholars, like the rest of the campus, had to suspend face-to-face instruction. Logan said that the pandemic has been trying for most faculty and students, but there’s an added level of chaos with a lot of the Re-Emerging Scholars facing housing insecurity, mental illness and more.

“Pattern disruption, finding what your new normal is and finding routines is just kind of amplified for our student population,” said Logan. “So many of them were already dealing with mental health issues or have PTSD because of incarceration, and now [self-quarantine is] basically incarceration light, and it’s stirring up a lot of familiar negative emotions.”

The recent change from face to face to online instruction due to COVID-19 has also made an impact on the program’s newest scholars.

“Our newest cohorts of students were just beginning to hit their stride with taking classes and showing up on time and showing that professional development,” said Logan. “Now they’re having to completely reinvent the wheel.”

In addition, Logan said that some of the students aren’t as tech savvy, which makes remote learning even more of a challenge.

“If you were incarcerated 10 years ago, then basically you’ve never experienced an iPhone, let alone Zoom meetings and teleconferencing and all that kind of stuff,” Logan said. “It’s a lot of work to try and triage and find some stability and help students overcome a lot of this adversity.”

During the second week of the campus closure, Logan said he had spent a couple hours a day talking to the students by phone, trying to be “a cheerleader for some of the insecurities that they’re experiencing.”

Logan said that some students have a fear that this will set them back both academically and financially, but that he and Miller are there to help the students navigate through it all. Their weekly check-in class has now been turned into a Zoom meeting at the same time they would’ve met on campus.

“It has allowed us to carry on, to carry on and to have something typical and have something that feels consistent,” said Miller. “And so that’s been nice.”

Their peer mentor program has also become completely online.

“Our peer mentors check in either via Zoom, via text, via phone call,” Miller said. “They’re maintaining the same level of contact, just not in person. So instead of going out to coffee, they’re having a Zoom coffee together.”

Logan and Miller have also been able to help the students set up study groups and find Re-Emerging Scholars interns to help facilitate those study groups. Logan hopes to set the right tone for the students so that they don’t have additional stress in their lives.

“Shit has hit the fan, and let’s see what we can do, and let’s see how we can adapt and overcome,” Logan said. “It’s not going to be perfect, it’s gonna be clunky, and neither Nich nor I are tech savvy ourselves. We’re going to [mess] this up multiple times, and it’s all we can do. We’re going to continue to do what we can do and continue to make progress and help any way that we can.”

While the transition hasn’t been smooth, Logan hopes the students understand the effort still going into the program.

“Everybody is adapting to the new normal and doing the best they can,” said Logan. “And showing our flaws and the fact that we’re just trying our hardest and not perfect alleviates some of the concern that they have to be perfect.”

Logan said some of his students were feeling timid about continuing their spring semester classes online and were thinking of dropping them, but Logan has encouraged them to keep going since online learning will continue through the summer and fall.

“You can step back and not take classes and not have to deal with the clunkiness of online learning, but at the end of this you’re gonna be in the exact same spot that you’re in now,” Logan said. “Whether it’s the end of fall or possibly at the end of spring, that’s a year of wasted time. Or you can continue to try and truck ahead.”

Nammavongsa said he will continue in school as he adapts to online classes.

“I’m trying to further my education, so whatever I can do possibly to make that happen, I will,” said Nammavongsa, who hopes to become a high school counselor, something he determined while in the program.

“[Re-Emerging Scholars] just guides you the right way,” said Nammavongsa, who plans to attend a four-year university. “They have the right amount of resources and a good amount of people to actually guide you the right way.”

Nammavongsa is thankful to the program for what it has helped him accomplish.

“Nich and Shane are the greatest people,” Nammavongsa said. “Without them and the program they’ve invested [so much] into, the time and effort they’ve put into it—I would really say that I’m blessed and grateful to have met them.”

Foston is pursuing a sociology degree, and she plans to use it to help others.

“I’m going to open my own advocacy group for parents who are going through CPS,” Foston said. “The way that we do it now only creates bigger problems.”

Like Foston and Nammavangsa, Collins also wants to pursue a career helping others.

“Something with child development or counseling,” said Collins. “Children that don’t have a voice that are impacted by the policies of having social workers over them in their house. Those are the people I want to help. I had to deal with that, so I know what that’s like.”

Even without Re-Emerging Scholars, Collins had always intended to go back to school, but the program has made the transition easier for him, and he, too, appreciates the support.

“Re-Emerging Scholars have been everything that a family can be,” said Collins. “It’s been sociable, diverse, encouraging and trying. In all aspects we have to re-emerge.”

by Rose Vega and Ben Irwin

Re-Emerging Scholars

Formerly incarcerated students walk a new path at City College

Three students at Sacramento City College aspiring to futures in public service—a high school counselor, child development professional and an entrepreneurial Child Protective Services case advocate—share a common past: They’ve all been formerly incarcerated.

They also share a common future: They’re actively working to create and live their visions of successful lives.

Mass incarceration is a national issue. While California has been touted in recent years for its work to end mass incarceration through legislation—realignment, revision of the “three strikes rule,” reducing penalties associated with nonviolent crimes and court-ordered prison population reduction—the Prison Policy Institute’s 2018 numbers on incarceration rates speak for themselves.

“The mass incarceration issue here in the state and across our nation is having this insane impact on our communities”

—Nich Miller, Re-Emerging Scholars co-founder and City College sociology professor

California recidivism rates—the rate at which criminals reoffend—have historically been among the highest in the United States, according to a June 2019 report from the Public Policy Institute of California.

The Re-Emerging Scholars program at City College is devoted to helping break the cycle of recidivism and institutionalization for formerly incarcerated individuals. It is in this program where these three students are redefining their identities, taking control of their lives and helping others.

Courtney Foston grew up with her parents in Carmichael before moving to Santa Cruz when she was 19 years old.

“I grew up in a middle class family. I didn’t grow up in a gang or anything like that,” Foston said. “Where I ended up—that’s all on me.”

Foston spent the entirety of her 20s in and out of incarceration for various criminal and drug offenses.

“I had no ambition to do anything,” Foston said. “I had never really felt a part of anything enough for it to be something that I was passionate about other than acting, and that all fell off when I started using drugs.”

A methamphetamine user, Foston said her life spiraled out of control when she watched her boyfriend and father of her young son overdose on heroin and die in her arms. She said she turned to heroin shortly after.

“When life happens that fast it’s so surreal,” Foston said of her boyfriend’s overdose. “Everything for me changed after that. Everything—it had to.”

Foston said her son also put things into perspective.

“That’s when I was like, ‘OK, you know what? I can’t do this anymore. This has to stop because I’m gonna end up like [her boyfriend]. My kid is gonna end up with no parents and just

memories of us, and I can’t do that.”

The Re-Emerging Scholars program at City College is devoted to helping break the cycle of recidivism and institutionalization for formerly incarcerated individuals. It is in this program where these three students are redefining their identities, taking control of their lives and helping others.

After her boyfriend’s death, Foston said she “was on a mission to not feel anything” when she had to do an eight-month jail sentence at Santa Cruz County Jail.

Foston explained that after someone starts getting arrested frequently, the second the cuffs are on, “You’re in jail mode. You’re incarcerated.”

The social structure in jail can be addictive, said Foston, and she quickly adapted to it.

“It sucks, but when you don’t see yourself going anywhere else, then it’s kind of like, ‘Well, I’m gonna make sure that when I’m in here that I’m comfortable, and I’m gonna make the best of it because it’s gonna keep happening.’”

Foston said that maintaining that facade of no emotion and always being tough was hard to break. That proved to be a struggle when she was grieving the loss of her boyfriend.

“I was in there when I was finally able to grieve because they made me, and so crying in there was hard,” Foston said. “You don’t want to be judged, but at the same time I had to feel what I was feeling to get it out, or it was going to eat me alive. That was the hardest time I’ve done.”

For Foston, incarceration was defined by dominance. She felt that for women it wasn’t about race but drugs and fighting.

“How you dominate is you come in with drugs, which puts you on the top of everyone’s list,” Foston said, “or you have to fight. You have to fight for your spot on top, or you just have to know enough people in there, and if you don’t, then you better get to know people, and you need to know your place.”

Foston said that every time she went to jail, she would become less and less emotional, which helped her to not feel guilty about committing a crime.

“It gets easier the more you turn off those emotions to get through,” Foston explained. “It comes to a point where you’re so dope sick that you don’t worry about anybody else and how they’ll feel.”

Foston added that every time she got arrested and sent to jail, she’d learn more and more from the other inmates.

“I’d get locked up. I’d go on my run when I got out. I’d get locked up. Learn a little more from whoever was still doing time in there, then come out and better my game,” Foston said.

During the eight-month sentence in county jail after the death of her boyfriend, Foston was transferred to Blaine Street Facility, a lockdown work program within the Santa Cruz County Jail, where she said her life changed for the better.

“I went to a special unit where you’re given milestones for completing courses,” Foston said. “You get a certain amount of time off your sentence. I did a bunch of milestone courses while I was there.”

Foston said she appreciated the amenities at the Blaine Street Facility—TVs, couches, nicer beds and the freedom to do one’s own laundry.

“It’s just different,” Foston said. “Made you want to stay.”

Foston said there were good parts and bad parts from her experience with incarceration.

“I learned to pay attention to my surroundings. Even though I was using it for evil before, now I can recognize it in other people,” Foston said. “When you’re locked up, all the faulty people are inside, and you can call them out for what they are. You can’t do that out here.”

Still, Foston said, she finds it tough to break away from the institutionalized mindset.

“You become very used to things working a certain way in a certain order.” Foston said. “Then when you get out and get all these other options, it’s scary. I didn’t even know what kind of food I liked. I didn’t eat for the first week—there were too many options. I wanted to go use so I could go back in. That’s how that cycle builds.”

Foston is one of about 150 people who’ve come to City College in hopes of turning a new leaf, where City College sociology professors Nich Miller and Shane Logan are actively making a difference on the ground level, helping formerly incarcerated students break the cycle through the Re-Emerging Scholars program.

Logan said the concept of Re-Emerging Scholars came in late 2016 after a sociology club field trip to Project Ascend, a re-entry nonprofit.

“I did a presentation there on the importance of education in recidivism reduction programs, and a lot of their clients were very interested in becoming students,” Logan said. “I ended up signing up about a dozen students that took two classes with me.”

Logan recalled the front row of those classes lit up with glowing and beeping ankle monitors.

“These were hands down some of the most engaged and enthusiastic students we ever had,” Logan said. “Any additional optional lecture I had in my classes, those were the only students out of the entire class that would actually show up to those additional types of things. Their enthusiasm was incredibly high, but their success rate was not.”

Logan and Miller, frustrated with the gap between enthusiasm and success, began to troubleshoot the barriers to success for these students.

“A lot of those students were dealing with housing instability, a lack of support on campus, not having an advocate for them in between them and their probation and parole officers,” Logan said. “Nich and I talked about how we could, instead of being part of the problem, be part of the solution—to contribute to the identity transformation that they so desperately wanted.”

Logan said the sociology club soon transformed into the Re-Emerging Scholars club, which evolved into the multifaceted program it is today.

“We’ve got a full cohort-based program,” Logan said. “We plug students in to a selection of GE classes, hand selected by us that we feel are the lead dominoes that can help make them more successful in both their personal and academic lives.”

Among the selections are accelerated classes in classes in English writing and personal finance.

“As they’re getting these financial aid checks, it will help them budget so they aren’t blowing their entire financial aid in the first couple months and then having to live off of Top Ramen or experience more housing insecurity in the future,” Logan said.

The next step in Re-Emerging Scholars is the internship program, said Miller, where he coordinates an internship within Re-Emerging Scholars as a mentor to new members, or an externship with a partner organization.

“So much of Re-Emerging Scholars is about identity transformation,” Miller said. “You see the apprehension, the disbelief, the worry and the fear in their eyes as they’re signing up for classes. And the interns are saying, ‘I know what the feeling was like, I know the doubts you’re having, but you’ll be in my shoes six months from now.’”

Foston was referred to Re-Emerging Scholars by her mother, who works with a local probation program. She now co-facilitates the sobriety society club—an arm of the Re-Emerging Scholars program—on Tuesdays and serves as a mentor to multiple new students.

“I get to help other people the way [Re-Emerging Scholars] helped me,” Foston said. “I’m not a positive person—that’s because of incarceration, because of the lifestyle I lived. I don’t trust anybody. Being put in this leadership position, my mentees would never guess that. I am so positive with them, and I make sure to build them up and let them know what they are accomplishing is good and they’re moving in the right direction. All of them are doing great.”

Foston’s positive attitude with her mentees has given way to new revelations for her own mindset.

“That helps me, to learn that, ‘OK, you can trust people,’” Foston said. “‘Not everyone is going to try to put you in jail or call CPS on you. Just trust.’”

Foston, Miller and Logan all said they understand the importance of timeliness in bringing in new members fresh out of incarceration. Miller said the program has found success thanks to their relationships with local parole and probation programs, and the hard work and dedication of their student interns.

“They provide us referrals of people who have recently been released, and we have our student scholar interns reach out immediately to get folks to campus, to provide a model and example of what their next move in life is going to be,” said Miller. “Part of this is immediately matching new students with peer mentors who have been trained to think about the cycle institutional mindset, because they all understand it, and they are there checking in once a week at least in a deep and meaningful way, and then a couple times a week to catch any worries, fears and challenges that are happening.”

Logan said early intervention means incorporating new students into Re-Emerging Scholars regardless of how the timing of their release lines up with the academic calendar.

“The recidivism rate is highest in the initial months upon release.” Logan said. “Early intervention is a powerful tool we have.”

Kenny Nammavongsa, 23, is pursuing a career to be a high school counselor. But six months ago his life looked different. At that point Nammavongsa had spent a little over four years incarcerated.

While Nammavongsa was incarcerated, a friend asked him what he wanted to do when he got out.

“I told him I wanted to go to school,” said Nammavongsa. “I didn’t know specifically what I was going to school for.”

His friend had received a letter through the mail about Re-Emerging Scholars and told Nammavongsa about it. When he went to check out City College campus, he asked about the program and walked into the office.

“The environment was so welcoming,” said Nammavongsa. “That was the first day I ever stepped into the office, and ever since I never turned back.”

Like Nammavongsa, sociology major Julius Collins learned about Re-Emerging Scholars through a group of friends that he saw at an Anti-Recidivism Coalition meeting.

“I was actually signed up at ARC, but I saw these guys, and they were talking about the program at Sac City and the Re-Emerging Scholars,” said Collins. “That was enough for me. Just to see those people came from where I came from—prison—to see they were here supporting each other was enough.”

According to Nammavongsa, one of the great things about the program is its variety of mentors, because the mentors have experienced what a lot of other students have been through.

“That’s what’s so good about a variety of mentors in that program—because every one of them is different, and you’re gonna find the mentor that works for you,” said Nammavongsa.

Collins is one of those mentors and has been since the start of his second semester. While mentoring is new for him, it has allowed him to connect with people he knew while incarcerated in a more positive light.

“This is a great opportunity for me. Some of the outreach programs that we do I am directly involved in seeing people from parole—people that I have seen in prison over the years,” Collins said. “They are seeing me now like, ‘You’re not back?’ ‘Nah, I’m working with the school and mentoring now. I’m trying to make a way for us.’ I think it is encouraging for them and gives them hope in a way to see that we don’t have to be the same way. We don’t have to be stuck in that institutionalized framework of thinking.”

Logan stressed the importance of helping students see their past not as a liability but an asset. He recalled a re-emerging scholar from the early days of the program whose last year of formal education was seventh grade before he spent the next 20 years in and out of prison involved with the Norteños gang.

“During those 20 years he had been treated like an animal and a number,” Logan said. “His role within that gang structure was to educate and indoctrinate new recruits. He’s now applying to grad school looking to be a professor. Those same skills he was using in his gang network are actually powerful tools that he can use to educate students in a prosocial way.”

Miller explained why formerly incarcerated student mentors and interns are the heart of the program.

“They have an experience that we don’t have,” said Miller. “That’s an asset for them to really be immediate and powerful contributors to our community immediately upon release, where they can communicate more effectively than we possibly could with many of the folks that are re-emerging into society.”

While enrolled in Re-Emerging Scholars, Foston has been living with her mother in Carmichael. She said her son was living there for over a year while she was incarcerated, and she did not want to uproot him when she got out.

“I commute, and it….” Foston paused to collect her thoughts. “It’s working for now.”

Foston said she’s hoping to find a place of her own, but despite the paycheck from her internship with Re-Emerging Scholars, there are still significant barriers.

“I don’t have any credit,” Foston said. “Anything outside of Del Paso Heights or some other ghetto, they want two lines of credit, and this certain credit score, so I’m like, ‘OK, I’ve got to start building that stuff up now.’”

Miller and Logan said that they have been making a lot of efforts to expand the program, with their eyes set on housing.

“The goal that we have is to work with community partners and with the Legislature to get housing specifically for Re-Emerging Scholars and for re-entry,” said Miller, “because one of the biggest issues that re-entry into a population faces is housing. Having stable access to employment and affordable housing along with higher education are key to the long-term stability and success of re-entry intiativeatives in this state.”

Housing most likely wouldn’t be located on campus due City College’s landlocked status, according to Logan, but he and Miller have begun initial conversations with housing community developments with Re-Emerging Scholars in mind.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the college’s closure as of mid-March, the Re-Emerging Scholars, like the rest of the campus, had to suspend face-to-face instruction. Logan said that the pandemic has been trying for most faculty and students, but there’s an added level of chaos with a lot of the Re-Emerging Scholars facing housing insecurity, mental illness and more.

“Pattern disruption, finding what your new normal is and finding routines is just kind of amplified for our student population,” said Logan. “So many of them were already dealing with mental health issues or have PTSD because of incarceration, and now [self-quarantine is] basically incarceration light, and it’s stirring up a lot of familiar negative emotions.”

The recent change from face to face to online instruction due to COVID-19 has also made an impact on the program’s newest scholars.

“Our newest cohorts of students were just beginning to hit their stride with taking classes and showing up on time and showing that professional development,” said Logan. “Now they’re having to completely reinvent the wheel.”

In addition, Logan said that some of the students aren’t as tech savvy, which makes remote learning even more of a challenge.

“If you were incarcerated 10 years ago, then basically you’ve never experienced an iPhone, let alone Zoom meetings and teleconferencing and all that kind of stuff,” Logan said. “It’s a lot of work to try and triage and find some stability and help students overcome a lot of this adversity.”

During the second week of the campus closure, Logan said he had spent a couple hours a day talking to the students by phone, trying to be “a cheerleader for some of the insecurities that they’re experiencing.”

Logan said that some students have a fear that this will set them back both academically and financially, but that he and Miller are there to help the students navigate through it all. Their weekly check-in class has now been turned into a Zoom meeting at the same time they would’ve met on campus.

“It has allowed us to carry on, to carry on and to have something typical and have something that feels consistent,” said Miller. “And so that’s been nice.”

Their peer mentor program has also become completely online.

“Our peer mentors check in either via Zoom, via text, via phone call,” Miller said. “They’re maintaining the same level of contact, just not in person. So instead of going out to coffee, they’re having a Zoom coffee together.”

Logan and Miller have also been able to help the students set up study groups and find Re-Emerging Scholars interns to help facilitate those study groups. Logan hopes to set the right tone for the students so that they don’t have additional stress in their lives.

“Shit has hit the fan, and let’s see what we can do, and let’s see how we can adapt and overcome,” Logan said. “It’s not going to be perfect, it’s gonna be clunky, and neither Nich nor I are tech savvy ourselves. We’re going to [mess] this up multiple times, and it’s all we can do. We’re going to continue to do what we can do and continue to make progress and help any way that we can.”

While the transition hasn’t been smooth, Logan hopes the students understand the effort still going into the program.

“Everybody is adapting to the new normal and doing the best they can,” said Logan. “And showing our flaws and the fact that we’re just trying our hardest and not perfect alleviates some of the concern that they have to be perfect.”

Logan said some of his students were feeling timid about continuing their spring semester classes online and were thinking of dropping them, but Logan has encouraged them to keep going since online learning will continue through the summer and fall.

“You can step back and not take classes and not have to deal with the clunkiness of online learning, but at the end of this you’re gonna be in the exact same spot that you’re in now,” Logan said. “Whether it’s the end of fall or possibly at the end of spring, that’s a year of wasted time. Or you can continue to try and truck ahead.”

Nammavongsa said he will continue in school as he adapts to online classes.

“I’m trying to further my education, so whatever I can do possibly to make that happen, I will,” said Nammavongsa, who hopes to become a high school counselor, something he determined while in the program.

“[Re-Emerging Scholars] just guides you the right way,” said Nammavongsa, who plans to attend a four-year university. “They have the right amount of resources and a good amount of people to actually guide you the right way.”

Nammavongsa is thankful to the program for what it has helped him accomplish.

“Nich and Shane are the greatest people,” Nammavongsa said. “Without them and the program they’ve invested [so much] into, the time and effort they’ve put into it—I would really say that I’m blessed and grateful to have met them.”

Foston is pursuing a sociology degree, and she plans to use it to help others.

“I’m going to open my own advocacy group for parents who are going through CPS,” Foston said. “The way that we do it now only creates bigger problems.”

Like Foston and Nammavangsa, Collins also wants to pursue a career helping others.

“Something with child development or counseling,” said Collins. “Children that don’t have a voice that are impacted by the policies of having social workers over them in their house. Those are the people I want to help. I had to deal with that, so I know what that’s like.”

Even without Re-Emerging Scholars, Collins had always intended to go back to school, but the program has made the transition easier for him, and he, too, appreciates the support.

“Re-Emerging Scholars have been everything that a family can be,” said Collins. “It’s been sociable, diverse, encouraging and trying. In all aspects we have to re-emerge.”

By Rose Vega | rvega.express@gmail.com

By Ben Irwin | birwin.express@gmail.com

Additional reporting by Sara Nevis.

By Rose Vega | rvega.express@gmail.com

By Ben Irwin | birwin.express@gmail.com

Additional reporting by Sara Nevis