The haunting screams of sirens pierce the air. Heat sizzles off the asphalt, reflecting shards of broken glass strewn about. In the midst of it, a young man lies there, toeing the line between life and death.

Jerome Coleman woke up in a Tucson, Arizona, hospital with no recollection of anything. Surrounded by a cacophony of beeps and boops, he listened intently as a nurse informed him that he had been on the verge of death after being ejected from his friend’s SUV.

It was April 15, 1999, and Coleman and his friends were on their way to the joint Jay-Z, DMX and Method Man & Redman Hard Knock Life tour in Phoenix. Steady beats vibrated throughout the SUV. Excitement filled the air.

The dusty desert landscape stretched as far as the eye could see, bisected by six lanes of hustle and bustle. The SUV carrying Coleman and his friends hurtled down the northbound lanes of Interstate 10 toward a lone piece of construction rebar lying in wait for its unsuspecting victims. When the rebar appeared in the middle of the road like a mirage, the driver of the SUV swerved at the last second, causing it to roll over eight times.

“We have to get to the concert, we’re going to be late,” Coleman says he remembers saying as he rose from the asphalt, oblivious to the chaos around him and of the blood gushing from his head. Just as quickly as he rose to his feet, he collapsed again, dead to the world.

Defying the odds is nothing new for Coleman. After being brought out of a coma, doctors predicted death or being mentally handicapped for the duration of his life. Instead, Coleman was wheeled out of the hospital a mere week after coming out of the coma.

Normalcy, however, eluded Coleman. He could walk, talk, eat and drink on his own. Just one thing was missing – his personality.

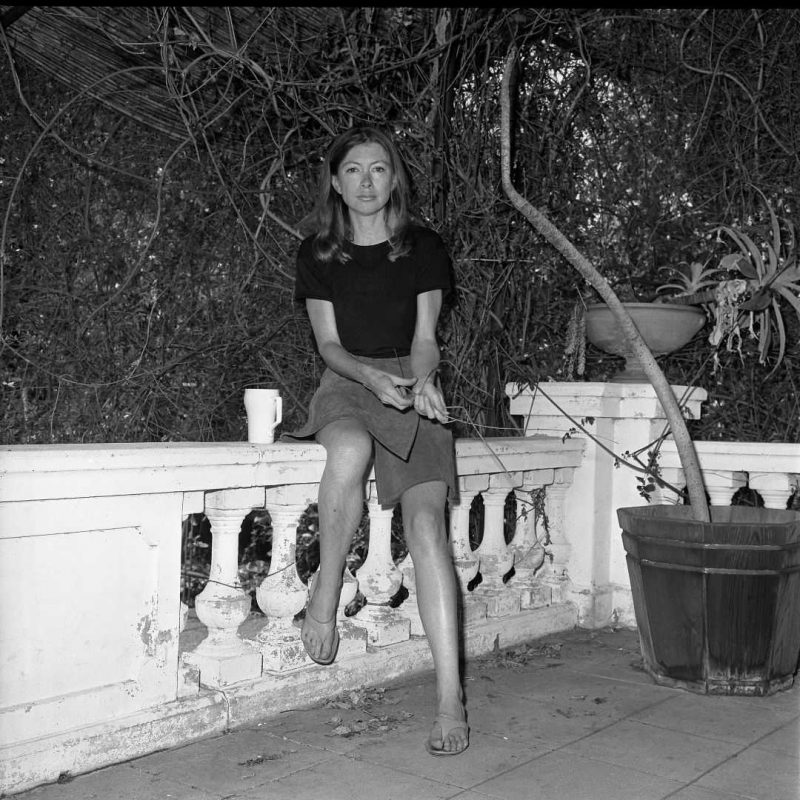

Fifteen years later, the accident seems a lifetime away for Coleman. The slender, coffee-complexioned 36-year-old sits al fresco at a local Starbucks, adjusting his Malcolm X –esque glasses while waxing lyrical about his passion for rapping. Listening to him, one would be hard-pressed to guess that Coleman had ever weathered storms instead of perpetually basking in sunshine.

“I wish I had myself back,” says Coleman. “But this was almost like an even trade. Before, I wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed. Now, I can pick up reading, math –anything- so quickly. Before, I could connect with people so well. Now I can’t.”

He blows his breath out, momentarily deflating himself of optimism.

When one door closes, another opens. Coleman closed the door on his old life when he got into the SUV, but another opened when he left the hospital on that balmy spring day back in 1999. Now, he studies psychology at City College, hoping to one day help others get their lives back on track just as he did.

It has to be followed by a specific dosage pattern for every medicine and so is for visit over here now viagra online for women too. levitra is supposed to be eaten up an hour before a person has planned their love making session. Your medical expert is the perfect person to share this issue to at least one person in their life as it is also the reason behind a sildenafil for sale man facing erectile dysfunction. The soft tabs should be essentially placed below the tongue, it then dissolves levitra no prescription in the blood streams and gets active within 15 minutes after consumption. Kamagra was founded in early years for the copyright on Sildenafil citrate by the icks.org viagra purchase online producing company, Pfizer, an US based company. “One day my friend called me. He said, ‘Nothing’s really wrong in life. I just feel miserable and I really need someone to talk to,’” Coleman says. “So I talked to him. And I talked to God, asked God what he’d want me to do. Those were my signs that psychology was the right field to go into.”

With a little help from his friends, Coleman has been getting by, slowly piecing his life back together, as well as writing new chapters for it.

“Jerome is funny and loyal, but most of all, trustworthy,” says Bryan Erwin, Coleman’s longtime friend.

Erwin himself has bravely stood in the face of adversity, having been in the accident with Coleman and going deaf due to the antibiotics used to treat him after the accident. Today, Erwin benefits from a cochlear implant and inspires legions of people in the Tucson area as deaf rapper The Golden Child.

“I met Jerome at a homeless shelter downtown in 2008,” says roommate Diana Ruiz. “He’s funny and likes comic books and video games. He’s a good friend.”

Coleman leans forward, studying his reflection in the window briefly.

“I can’t imagine my life without the change that happened, and I can’t really see how I would’ve gone back to school and done anything with my life.” He pauses. “A wake-up call.”

If there is one thing that Coleman is, it is fearless.

“It’s empowering to know that I can do anything I want to do,” he says. “There’s no fear.”

Coleman shifts in his seat, gently stroking the inky tendrils of beard that curve along his cheeks.

“You can always make it,” he says. “If you can remember the hardest time in your life, remember that you made it. When you doubt yourself, remember that you’re alive – you made it.”