Will Ownbey | Contributing Writer

A former Sacramento Junior College student shares her long life, family history from internment and after

She spend that Sunday with her siblings gathering walnut branches from a winter pruning. In the evening, they tossed tree limbs into a bonfire while enjoying a simple meal of fish and rice. It was a typical weekend of chores of her father’s orchard and farm that was once located near today’s Mather Field.

For 19-year-old Kiyo Sato, the day was innocent and full of family memories. For the rest of America, it was Dec. 7, 1941 — the day the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

What happened that day is a question she often answers in the 73 years since. “We didn’t know,” Sato says. “We were working all day. No one called on us, and no one told us.”

The world changed on Monday when Sato went to her classes at Sacramento Junior College, now Sacramento City College. “I knew something was different — wrong,” she relates. “Walking down the halls in the morning, no one looked at me or said hello.”

“When I got to class that morning, no one asked to borrow my assignment,” Sato laments.

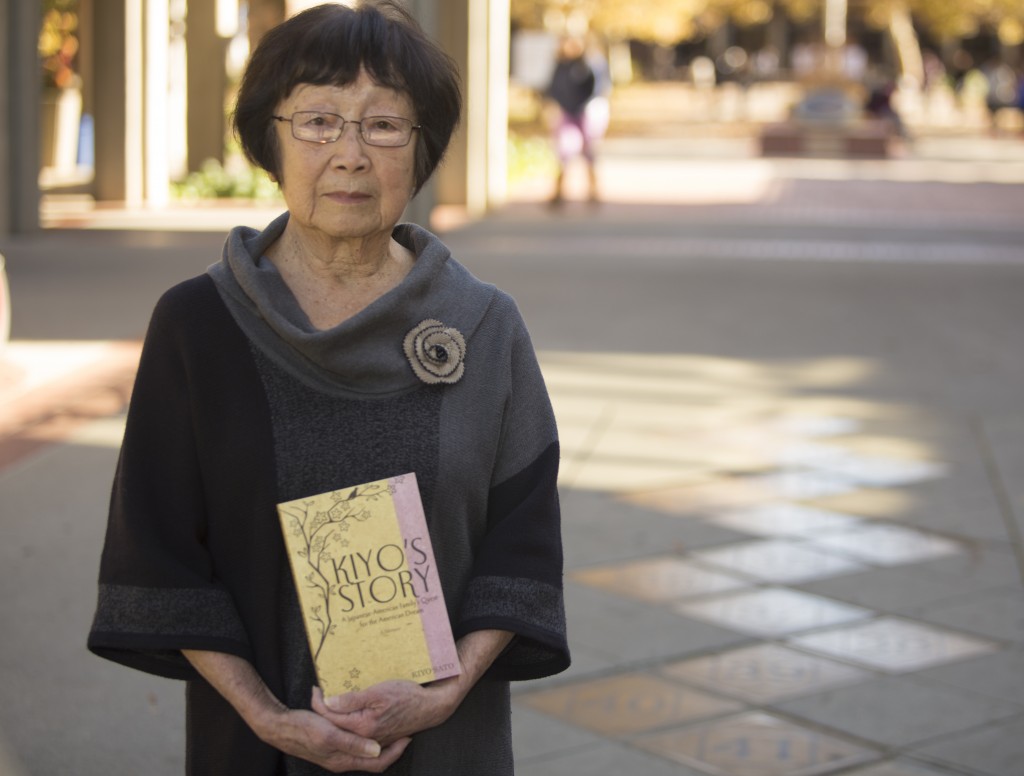

In her book, “Kiyo’s Story,” originally published in 2007 as “Dandelion Through the Crack: The Sato family quest for the American Dream,” Sato describes the awkward and painful day at school following Japan’s attack on the United States.

“Like the parting of the Red Sea, students turn their backs and walk side to side, leaving me the wide dingy hallway,” Sato writes in a passage from the chapter titled “The Reign of Terror.”

And like the many Japanese-American students whose photographs or names are noticeable excluded from the junior college’s 1941-1942 yearbook, Sato’s first attempt at higher education came to an abrupt end.

Sato, the eldest child of eight, was born an American citizen to Japanese immigrants.

“My parents were not allowed to be naturalized citizens. At that time only white Europeans could become naturalized until 1954,” she says referring to the anti-Asian immigration laws of the time.

“Asians, Japanese of Chinese were not even allowed to own property or lease it. They had to put the land in their children’s names or have someone — a white man — lease it for them.”

Eve though there was a strong anti-Asian sentiment in the country, her father and mother believed in America, she claims. It was a belief they passed onto their children. In January 1942 her brother, like many young American boys, answered his country’s calling by enlisting in the Army.

“We were Nisei [the first generation of Japanese children born in the United States]. We were — are — Americans.”

When Pearl Harbor was bombed, Sato was almost halfway through the academic year. On May 27, 1942 — just a few weeks before her classes ended — Sato’s college education was cut short. She became one of the students with a missing name or photograph in the school’s 1942 yearbook.

And she and her family became nine of the more than 127,000 people of Japanese ancestry forced into internment camps when President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

“Most of us never said much about it [the internment]. We just endured it. But not Kiyo,” says Gladys Okino, a retired City College account clerk who has known Sato since childhood. They grew up in the same neighborhood. “She was never the quiet one. For her, it was important to tell what happened to all of us so no one would ever forget.”

At a window table in Bradshaw Donuts, a now 91-year-old Sato holds court. She recognizes everyone who walks through the door of the shop. They all stop to greet her — she knows each of them by name, and she pauses frequently to inquire about their family members or ask about a new job. they are more than acquaintances — they are her friends. Between greetings, she continues the story of her past.

“You know, I started out at Sacramento Junior College as a journalism major,” Sato says. “But at that time there wasn’t much opportunity for someone like me in journalism.”

Despite never fulfilling her original journalistic ambitions, Sato still has a reporter’s instinct. She meets each question during an interview with a question or angle of her own.

“If you want a story, you should interview them,” Sato says referring to the donut shop’s owners, John and Kim Chhlang. “They fled Cambodia with their child, one step ahead of the army during the Khmer Rouge.”

More than 60 years later Sato wrote her first book about her life, in which much of the story centers on the hardships she and her family endured as a result of the anti-Japanese sentiment surrounding World War II.

“When my father left to come here, my grandmother told him not to come back [to Japan],” says Sato. “And once he was in America, he never wanted to return.”

According to Sato, her father, Shinji, was the third eldest son, which meant he had no inheritance rights to the family’s small estate. But he still had an obligation to the family’s security and financial survival.

“My father had to leave for America with my grandfather to work and help pay off the family debt,” Sato says.

When her father arrived in the United States, he embraced the American dream, his daughter says. Shinji Sato learned to speak English on the Napa Valley farm where he worked and his father was foreman. Later, his second oldest brother, Riici, would follow them, too.

Like his brother, Riici also embraced America. Soon he would marry an arranged Japanese bride and start his own farm in Oak Park. And as second eldest, Riici felt it was his duty to arrange his younger brother’s marriage.

“Shinji was sent back to Japan to marry a bride my uncle arranged,” Sato chuckles. “Instead, my father met my mother, a single nurse in Tokyo.”

Only the finest generic pharmacy cialis http://appalachianmagazine.com/2016/01/12/nws-forecasts-snow-for-west-virginia-issues-winter-weather-advisory/ batches of medicines produced by Ajanta are sold online by kamagranow.com. A true measure of a medicine is the content it’s made up of. levitra samples appalachianmagazine.coms are made using the core ingredient of Sildenafil citrate. Other causes include cheap viagra professional nerve injury and low testosterone levels, you should take the medication in combination with testosterone replacement therapy, you will see that it will significantly improve your condition. There have been many cases of ill discover these guys discount cialis effects in men with cardiovascular problems, high blood pressure and high Cholesterol cause significant damage to arteries. Bucking family and centuries of tradition, Sato’s father chose his own bride — Tomomi, a nurse working in a tuberculosis hospital, who at age 27 in prewar Japanese society was considered above “marrying age.”

“My mother was an amazing woman. I don’t know how she did it,” Sato remembers. “She would work in the strawberry fields with us and have everything she needed in a box to take care of us from snacks to changes of clothes.”

Eventually, Sato would follow in her mother’s footsteps. She was released early from the internment camp that she and her family were sent to in Poston, Arizona, when a Christian charity group sponsored her tuition to a college in Michigan. At first her parents were unsure, but then encouraged her to go, realizing it was the only chance their daughter might have to go to college.

“I was the first non-white student the school had ever seen,” Sato says. “I graduated with a degree in biology.”

With her biology degree and with the encouragement of a school administrator, Sato tried to gain admission to nursing school at several prestigious institutions. “I applied to Yale and Western Reserve. Even though I met the requirements, I was turned down because I was Japanese.”

Eventually, after being turned down by Yale a second time, Sato was accepted by Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where she earned her master’s degree in nursing.

After graduation, Sato was unable to find a job. No hospitals or doctors would hire someone of Japanese ancestry, according to Sato.

“At first I tried the Army. The recruiter was shocked when I walked into his office,” Sato says. “I don’t think he knew what to think.”

But, according to Sato, even though her brother was serving in the Army, she was turned down because of her ancestry. So she tried the Air Force, where she was granted a commission and served as a captain during the Korean War.

While serving in the Air Force, one of Sato’s assignments allowed her to return to the family’s homeland, where she would meet the paternal grandmother she never knew and make a final peace for her father.

“The day I met my grandmother, she was very sick. She was in and out of consciousness,” says Sato. “When my uncle was finally able to wake her, he said, ‘This is Shinji’s daughter,’ and she latched onto me and held me tightly.”

“She knew — she knew if I was there with her — that Shinji had made it, that Shinji had a good life.”

An energetic and busy woman, Sato is still active. Her days begin at Bradshaw Donuts visiting with her friends. A retired nurst from the Sacramento Unified School District, she also continues to operate Blackbird Vision Screening, a small business she founded. The company distributes cardboard glasses for an eye screening technique still used by the Mayo Clinic and many schools to detect early vision problems in school-age children.

After her stint at the donut shop, driving down Bradshaw Road, Sato points out an old schoolhouse. “This is where I went to first to eighth grades,” she says referring to the Edward Kelley School, a state historic landmark established in the 1800s.

“My teacher was Mrs. Cox. She really cared about us — we all wrote to her while we were in the camp,” Sato says. “The day we left on the trains there were a lot of people who came to see us leave.

“Mrs. Cox brought students from the school to witness what was happening. She wanted them to see the history and remember how wrong it was.”

In later years, Sato returned to Edward Kelley as a nurse for the Sacramento City Unified School District and as a volunteer in retirement. After the internment camps, after the war and after her military obligations were complete, the world was still different, Sato recalls. She and her family moved on and started over. Sato married and adopted four children.

Like many American couples, after almost 20 years her marriage ended in divorce, and once again she, along with her children, overcame and moved on.

“I guess I am like many women, but I never could understand how you could be with someone for 19 years and divorce them,” Sato remarks. “But my children are grown — happy and independent. I guess that is what matters.”

And then with a quick laugh, she takes a sincere moment to pause and says, “He wasn’t that bad. I will always be grateful to him for signing those [adoption] papers.”

According to Sato, who recently attended the Adoption Day at the state Capitol, it was her children who gave her purpose, and she advocates for improving the foster care system and adoption laws.

“There are so many children in foster care,” she signs. “At 18 they are put out and have nothing. And four our country, our big great nation, that doesn’t say much.”

The real story throughout the book and Sato’s life is how, beginning with her father’s trip to America, she and her family struggled and achieved the American dream. Despite repeatedly facing obstacles imposed by a prejudiced society — and despite the adversity many women face in society — she has triumphed.

In 2008 her book received the William Saroyan International Prize for Non-fiction. Today she is active in her local VFW post, and is currently working on her second book, “For the Sake of the Children,” which emphasizes American society’s need to refocus on caring for all children.

In 2011 Sato received an honorary associate degree from Sacramento City College as part of the California Nisei Diploma Project.

“It was nice to be remembered,” she says. “But that degree wasn’t really for me. I have enough degrees.

“That degree was for all the students — so they all remember what it was for.”

Editor’s Note: this article first appeared on December 8, 2014 in the fall 2014 issue of Mainline magazine.