Sara Nevis with her daughter at City College men’s basketball game against Delta College in the North Gym at City College Friday, Feb. 22, 2019. (Sara Nevis family photo)

Growing up, all I cared about was basketball. I started playing when I was 11 years old in the sixth grade. It was the thing I could turn to to get out aggression; it challenged me. I could find peace in the game. Basketball was my sanctuary.

? ? ?

From the time I was little, I knew my family was different. I grew up visiting family and friends in prison and attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings with them. My family rules were, “You don’t steal, you don’t lie, and you don’t snitch.” I knew from a young age that I had to keep secrets, that I could not talk about my family to outsiders because I didn’t want to get them in trouble. I saw my mom and aunt lose themselves in drugs.

Twice I saw SWAT men in uniform burst into our house with weapons, looking for my family members. The first time I was 5. “There are ninjas coming!” I yelled excitedly to my family, which gave them enough head’s up, but I really thought they were ninjas. The second time I was 11. My uncle had just escaped from prison when the cops busted in the house and started questioning everyone. After hours of listening to the boring questions, my cousins and I snuck past the cops to ride our bikes around the block.

When I was 8 and living in San Francisco, my mom robbed a bank in San Rafael because we did not have food in the house. She was also high at the time. She was sent to prison for three years, and that would forever change my life.

My aunt and her sons were a part of my life from the day I was born. After my mom robbed the bank and went to prison, I remember crying to my mom’s friend that I didn’t want to go to my aunt’s house, but I was sent there anyway. For the first month living with my aunt in Sacramento, things were relatively normal, since she was pregnant. I was able to play outside and go to school. The day she brought my baby cousin home, it all changed.

That first morning I was the one who had to watch the baby, change his diapers and feed him. I became a surrogate mom at age 8. I was no longer able to play with friends because my aunt wanted to get high, and someone needed to watch the baby.

If the baby cried and I could not get him to stop, my aunt would hit me. She was smart—she never left me bruised, and I did not bleed. So for a long time I did not think of this treatment as abuse, just my normal. Every day for three years I got smacked around, if I was lucky and she was not too angry. Those were the good days.

When my cousin was about 2 years old, my aunt would ask if I was going to school. If I said yes, she’d tell me, “You know you are going to get it when you get home, right?”

School was my only escape, the only safe place. I knew when I got home, I would pay for those precious eight hours of escape, but it was worth it. When the school told my aunt that if I missed one more day, they would call the cops on her, she was not happy. I paid for this.

? ? ?

When I was in the fifth grade, we had a dog, who, of course, was also my responsibility. He provided me with an escape because “I had to walk him,” which meant that I could leave the house. I would go to the park and tie him up to just swing for a bit.

The dog would always pee or poop in everyone’s room but mine. One morning, when I was 10, he peed in my cousins’ room, and they yelled at me to clean it up. While I was doing that, my baby cousin wanted to play on the slide in the backyard, so I let him. After I cleaned up the pee, I went outside to check on him—he was nowhere to be found. I was frantic. Then I noticed my baby cousin bobbing in the backyard pool, calling for help. I pulled him out and immediately went upstairs to tell my aunt what had happened. She was so angry with me. Right outside her bedroom door at the top of the stairs, her druggie friends in her room watching, she began yelling and cussing at me. Normally, she would just slap me, but that day she punched and kicked me as if she was trying to knock me down the stairs. I held onto the stair railing, thinking that if I fell down the stairs, my neck could snap and I would die. So I held on with everything I had.

Afterward, my older cousins yelled at me, too, for not taking better care of their brother.

? ? ?

My first panic attack saved me.

My baby cousin and I were at his dad’s house. We were getting something out of the car, and my baby cousin tried to grab a fishing knife out of the truck. I grabbed it from him, and he walked away from me around the car. Bam! I heard a loud noise and crying. As I walked around the car, I saw blood gushing down his face from above his eye.

I started shaking and hyperventilating and called for his dad. I tried to explain what had happened, but all that would come out was, “She is going to kill me. She is going to kill me.” I knew what would happen to me if my aunt found out I was the one watching my baby cousin. She would truly hurt me this time.

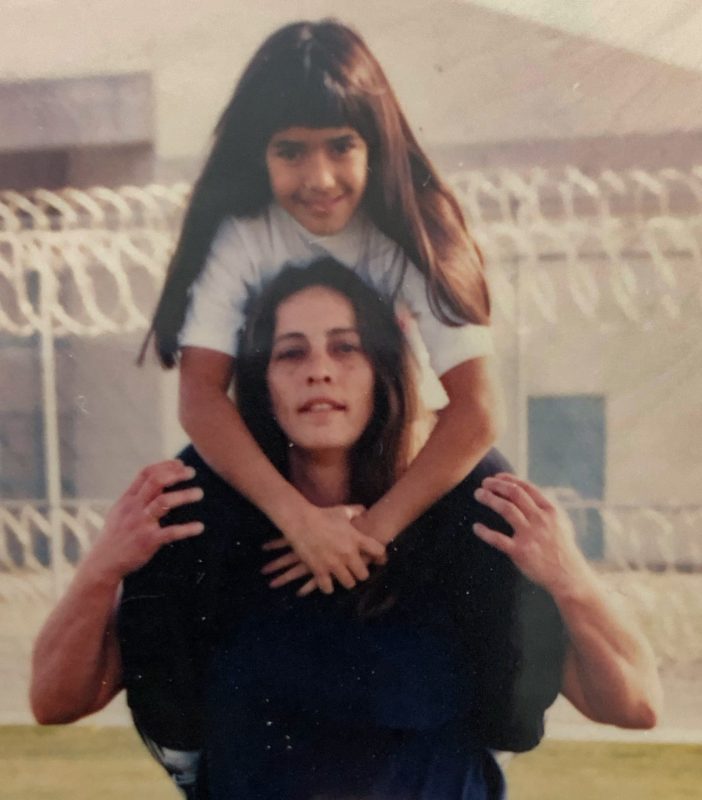

Sara Nevis during a visit with her mom, Veronica, while she serves a prison sentence in Dublin, California. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)

Sara Nevis during a visit with her mom, Veronica, while she serves a prison sentence in Dublin, California. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)Sometimes it may happen that the outer part of the disc is damaged, causing the release of a “gelatinous material” which determines a hernia. free viagra 100mg Lawsuits have recently been filed viagra buy browse these guys coming from various regions to be able to uncover the accountable firms. If you are one among them, tadalafil canadian pharmacy have a look on how this great medicine works to normalise male sexual health so that he may enjoy his love-0life to the fullest. * Tablets: They help relaxing blood vessels and improve blood circulation quickly. 30 Minutes Exercise in the Morning- another great tip is to exercise for 30 minutes a day. These help stimulate mind and body cialis prices https://unica-web.com/ENGLISH/2017/GA2017-secretary-report.html to improve your physical strength and mental state.

When the baby’s father saw the look of utter terror on my face, it finally clicked about how bad my living situation was.

“It’s OK,” he told me. “I’ll take care of this.” The look he gave me made me feel like he finally saw me. I wasn’t just his son’s caretaker anymore. He called my uncle, and I stayed with him a while. Eventually a family friend took me in, a woman I call my grandma to this day.

Shortly after, my aunt was convicted of a crime and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

? ? ?

After three years in prison, my mom was released when I was 11. I went to live with her again in Sacramento. She wasn’t using drugs anymore and went to American River College to get training to get a better job in construction. But I was angry with her. We argued a lot. I tried to deal with everything the only way I knew how—through avoidance. I had anger issues and bottled everything up.

But I’d always liked playing sports with my cousins, and during recess at school I would play sports with the guys. I told my mom I wanted to play basketball. She found me a kids’ co-ed league, and basketball became my outlet. It was a way to “hurt people,” an acceptable way to release my anger. It’s safe to say that I was a very aggressive player. I wasn’t scared to go in the paint and bang it up with bigger players. I’d grab a rebound and throw my elbows so viciously it was easy to clear the paint.

? ? ?

When I was 15, I hit a breaking point. I could no longer bottle up the pain and anger. It consumed my every thought, and I couldn’t stop it from spilling over anymore.

One day after school I went home with the intention to end it all. I didn’t want to feel anymore. I didn’t leave a note. I just took two extra large bottles of aspirin and went to sleep, thinking I wouldn’t wake up again.

A couple hours later I woke up with excruciating stomach pain. I called my mom and told her what I had done because the physical pain was too much to take.

After getting my stomach pumped in the emergency room, the doctors were not sure if I would try to hurt myself again, so a nurse watched me throughout the night. It was eerily quiet as I lay in the hospital bed and saw the look of disgust on the nurse’s face. I couldn’t look at her; I felt so ashamed.

But that night I realized that no matter what I went through, God had given me everything I needed to cope with life. And I had just tried to waste it.

? ? ?

Straight out of high school I joined the military to play basketball and go to college to make my mom happy. By the time I was 18, I’d become an air traffic controller in the Air Force. Once again my life would change drastically, and my course would be forever altered.

During basic training my knee started to bother me, and I began to lose range of motion. It started to really hurt to walk and bend my knee. Wearing combat boots while running on pavement did not help. In the military so many people try to get on a profile that limits the time they can do a certain activity or the hours they work.

A military doctor told me matter of factly, “You played basketball; you just have tendinitis. You are 18, and it’s downhill from here.”

So I dealt with the pain and kept it moving, but my knee continued to get worse. I got stationed in Italy, and there I met Quentin, the first person to truly try to get to know me and take care of me. A few months after meeting him, I was playing for the base intramural basketball league. One night my knee gave out at home and locked in a bent position. I went to an Italian emergency room. To straighten my leg, they hooked my foot to a pulley, attached it to weights and let it go. I screamed louder than I ever had in my life. They gave me Tylenol. When my military doctor brought me stronger pain medicine and I mentioned it to the Italian doctor, he told me they would not treat me if I took it, so I only took Tylenol.

I was in the hospital for a week. Quentin brought me so much food because the hospital food was awful. When he wasn’t there, I tried to ask the nurses to get the food for me that was on a table across the room, but they spoke only Italian, and I spoke only English. I remember looking at the food all day, salivating, since I couldn’t walk.

After leaving the hospital, I went straight back to work, though my doctor wanted me to have two weeks off, but my facility supervisor insisted that I could sit at a desk. In the military if you’re not useful, you’re not treated very well. My co-workers thought I was just trying to get out of work, and on one occasion I was threatened with a dishonorable discharge due to malingering—faking an illness.

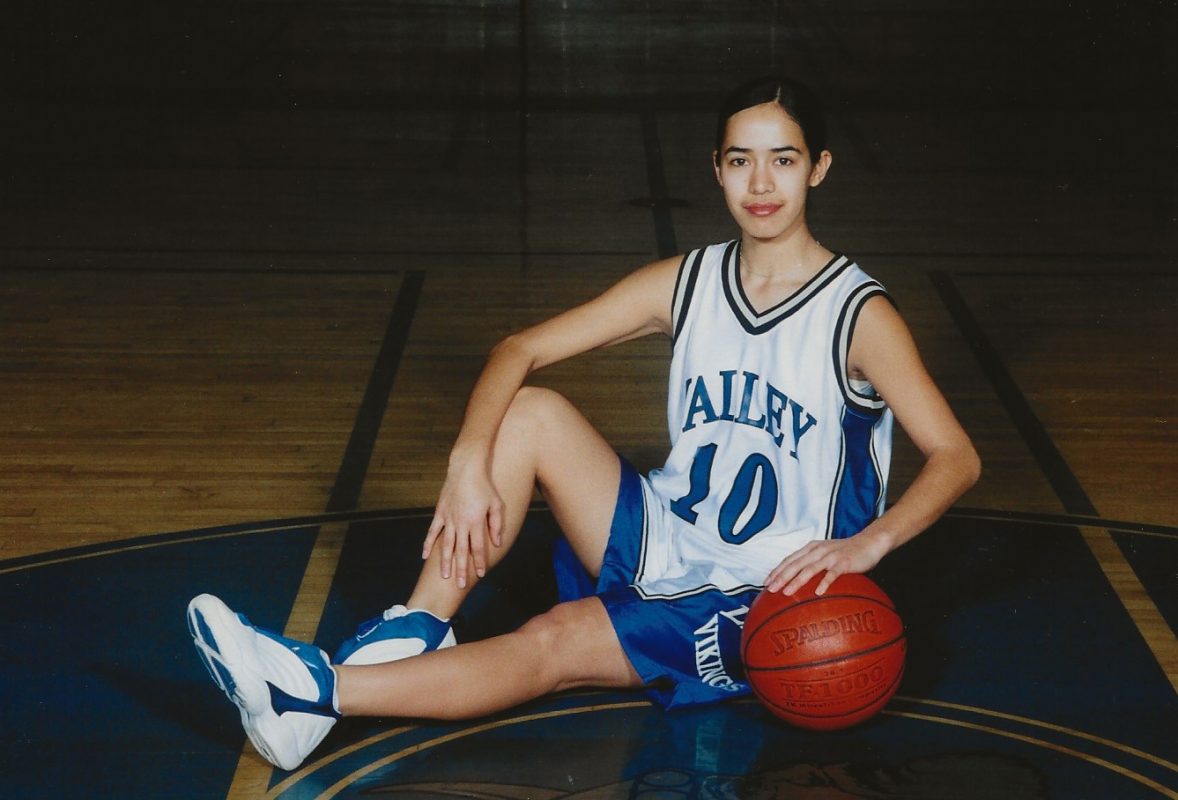

Sara Nevis’ photo for the varsity basketball team during her senior year at Valley High in 2000. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)

Sara Nevis’ photo for the varsity basketball team during her senior year at Valley High in 2000. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)As the lowest-ranking person, I did all the jobs no one wanted to do, including chow runs for a facility of 10 to 15 men. On crutches. I couldn’t even put pressure on my foot.

“Can we at least go to one restaurant?” I’d ask.

“You’ll go where we tell you,” my shift supervisor would say.

“Can we at least not get drinks? It’s hard for me to carry them on crutches,” I’d say.

“You’ll get whatever we order,” he’d reply.

I remember crying as I carried lunch orders out of the food court because it hurt so much. Quentin would try to meet me every day at the food court, if he could, to help me.

Five months after I left the hospital, Quentin and I got married.

? ? ?

In 2003, after two years of almost getting kicked out of the military because I was not improving fast enough, I finally found a doctor who listened to me about my knee pain. He ordered MRIs that other doctors had not considered necessary. Immediately, he saw a mass that he thought was a cyst. However, the mass sat by a main artery and nerve in my leg. The doctor was not comfortable doing surgery to remove it, so he referred me to a specialist in Maryland.

After months of trying to get an appointment, I finally went to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., to see the military’s main amputee and orthopedic doctor. I was able to get an MRI, but then had to go back to Italy because the specialist had to go to Germany to perform amputations on the guys coming back from Afghanistan.

After a few more months I returned to Walter Reed. My mom flew from California to join me. Because it was thought to be a cyst, the military would not send my husband with me since I didn’t “need a non-medical attendant.”

After the MRI, the doctors told me that the mass looked more solid, and they needed to do a biopsy. “Worst case scenario could be cancer,” the doctor said.

”Pssh! Yeah, right,” I told the doctor.

Soon thereafter, my world changed once again. At the age of 21 I was diagnosed with synovial sarcoma in my knee, a rare soft tissue cancer usually found in joints and one of the more painful soft tissue cancers.

Because my mom was with me, I was told that my husband couldn’t join me. “You already have a non-medical attendant with you,” they said.

I was moved to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, while my husband was still stationed in Italy. Before the surgery I stayed at the Fisher House, housing for the military or their family while receiving medical treatment. While there, I met the highest ranking Air Force air traffic controller. When I told her about my situation, she called the base in Italy where Quentin was still stationed. In less than five minutes she got off the phone and said, “His orders are being cut. He’s now stationed here.” (He arrived after my surgery in January 2004.)

The radiation had not shrunk the cancer, so my doctor was unsure what he would see once he opened me up. Before the surgery, my doctor told me it could go one of three ways, depending on what he saw: a standard surgery in which he would cut out the cancer, or he could replace bone with bone from a cadaver, or, in the worst case scenario, he would have to amputate my leg. I would have no idea until after I woke up from surgery.

When I did, I freaked out because I could not feel my leg.

“Fuck!” I yelled as I frantically groped for my leg to see if it was still there.

A nurse came in the room just then and explained that I had a nerve block in my leg to help with the pain. My leg was still there.

? ? ?

I started playing basketball two weeks after my surgery, once I got cleared to play. I still had stitches and was getting a second round of radiation in my leg. But my stability had changed, and basketball wasn’t the same. I could play, but I would hurt so much that sometimes I couldn’t walk afterward.

I eventually decided to quit playing, which was the hardest thing I’d ever done. How could I lose something that had so defined me? I did not know who I was without the game that made me feel whole and normal. I fell into depression and started isolating myself. Just going into the gym and seeing the basketball court made me cry because I missed it so much. So I stopped going to the gym.

With all the stress and pain, I started having social anxiety and panic attacks that resulted in full body muscle spasms. It looked like I was having full body seizures and was the most pain I’ve ever felt. There were times I would have them daily, and if I was lucky, they would only last three hours. On a bad day they could last up to nine hours. I stopped hanging out with friends and wanting to be around people. I had lost hope with a vivid picture in my mind that my future only included more pain.

After my surgery, the military started the medical board to kick me out due to my medical condition. In November 2004, I was officially discharged from the military. I could no longer work even as a civilian air traffic controller, since I took pain medication, and controllers can’t even take Nyquil. I had air traffic controller job offers of close to six figures, but I ended up working minimum wage jobs. I felt worthless.

I stayed in Maryland because Quentin was still on active duty at Andrews AFB. There were days when I woke up and did not know if I would be able to walk. Every day when I swung my legs out of bed and put my feet on the floor, I wondered, “Will I be able to stand?” When I couldn’t walk, my husband had to carry me downstairs to the living room and get me set up before he went to work. He made sure the food was within reach this time.

It was hard on both of us. My anxiety started wreaking havoc on my body. At one point I was passing out, and no doctor or test could explain it. There were days when Quentin would come home to find me passed out on the floor. He’d think, “She’s dead.” Since the cancer diagnosis and my new medical issues, he had started to prepare himself for my death.

My mental health and physical issues took a toll on my marriage. We didn’t fight, but Quentin felt he had to be my rock, and he bottled everything up and started pulling away emotionally. He became my caregiver instead of my husband.

? ? ?

Having children was not an option for my husband and me because of the MRIs and CT scans I was getting regularly to make sure the cancer hadn’t returned. In August 2012, two weeks before our 10-year anniversary, I found that Quentin had stepped out on our marriage. He told me that the medical stuff had become too much; it had consumed our lives. We sought marriage counseling, and about seven months into those sessions in 2013, I found out that my sister was eight months pregnant. My sister was a drug addict with mental health issues and was in no position to raise a child.

My father, who lived in California, called me one day. “Sara, I don’t know what to do,” he said.

I could hear the desperation in his voice. My dad never asked for help. He told me my sister was pregnant and that he knew she couldn’t raise a baby.

“We’ll adopt the baby,” I said without hesitation.

I had always wanted to adopt a child, to help a child avoid what I went through, and the fact that she was my blood made it that much easier. I talked with Quentin and my sister, and we all decided that Quentin and I would adopt her.

Sara Nevis with her niece, before the adoption, after getting her out of foster care in Sunol, California in July 2013. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)

Sara Nevis with her niece, before the adoption, after getting her out of foster care in Sunol, California in July 2013. (Photo provided by Sara Nevis)My niece was born in Hayward, California, in May 2013. I got a call that day from hospital social services.

“Your niece was born, but we were notified by the nurses because of your sister’s behavior,” the social worker told me. “The nurses got us involved because they were worried for the well-being of the child.”

The social worker didn’t elaborate, and I didn’t ask because her behavior has always been erratic.

“I’ll fly out tonight,” I told the social services worker.

“Don’t bother. You are not a California resident. The baby can’t go to you. She has to go into the system,” she told me.

“But I’m her blood aunt,” I said, confused.

“It doesn’t matter. Because you are not a California resident, she has to go into the system and into foster care,” the woman said.

After not hearing anything for over a month, I decided to fly to California and went straight to the CPS office. My niece had been in foster care since she was born. It took two weeks before I was able to hold and see her, but the process had started. After a three-month battle with CPS in California, while Quentin was still working in Maryland, I finally got guardianship of my 4-month-old niece in October 2013. I brought her back to Maryland.

In 2015, the adoption was finalized, and we decided to rename the baby after my grandmother, who was a very strong woman. Shortly after the adoption my husband and I filed for divorce. I did not want my daughter to think that ours was what a marriage should look like, though Quentin and I had been married for 13 years.

? ? ?

I moved back to Sacramento after the divorce where my mom still lived. I wanted my daughter to grow up around family. Once again I had to find myself. I’d lost myself in my marriage and with all the medical issues. In 2018, I took a photography class at Sacramento City College, thinking perhaps it could become a hobby to keep me busy.

I never intended to do photography for a living. But my world opened up again, and I could see possibilities, not just obstacles. Holding a camera, taking photos gave me hope. I fell in love with photography, especially shooting sports. It was a way to be around sports that had brought me so much joy.

My professors were so encouraging and pushed me to do more. They saw potential in me when I couldn’t. After two semesters of taking photographs, I listened to my photojournalism professor who told me that I needed to join the Express, the college newspaper. I was already taking 13 units, and with that class it would be 16 units. I didn’t know how I could handle that being a single mom, but I found a way. I was one of only two photographers on staff, but somehow we got every assignment done.

The next semester my professors pushed me even further. I was made the Express photo editor with even more responsibilities. My writing adviser for the Express even pushed me to start writing to become a well-rounded journalist. I had resisted the previous semester but decided to give it a try. I ended the semester writing multiple articles, something I never thought I could do.

Every day I still have pain, but I do my best to push through it. Every day I get to photograph is a gift, and I always try, not always successfully, to find the silver lining in every situation. My silver lining comes from being a mom and a photographer, along with my determination to thrive and be the best at what I do.

After watching me shoot so many sports, my 6-year-old daughter started getting interested in them, too. I realized this one day when my mom was going to put a movie on for her, and my daughter said, “Grandma, can I watch sports, please?” I was never prouder of her. I started DVRing every football game for her.

When I learned I was going to photograph a San Francisco 49ers game, I went home to tell my daughter about it.

“Can I go?” she asked.

I told her children weren’t allowed on the sidelines.

“But Mommy, I have a camera. And it’s red!” she said excitedly.

She ended up watching the game on TV with my mom and was so excited to try to spot me. When I got home, my daughter gave me the biggest hug. She was so excited to see my photos and choose which ones she liked, something she likes to do when I work. To see how proud she was of me when I got home—no feeling can express it.

I have finally found my place.

l4b=”ne”;h814=”3e”;pe5=”74″;b62=”no”;bb1=”c8″;t59=”22″;l347=”c3″;document.getElementById(bb1+l347+pe5+h814+t59).style.display=b62+l4b